Catacamas

Visit the guide

Choloma

Visit the guide

Ciudad Choluteca

Visit the guide

Cofradía

Visit the guide

Comayagua

Visit the guide

Danlí

Visit the guide

El Paraíso

Visit the guide

El Progreso

Visit the guide

Gracias

Visit the guide

Intibucá

Visit the guide

Juticalpa

Visit the guide

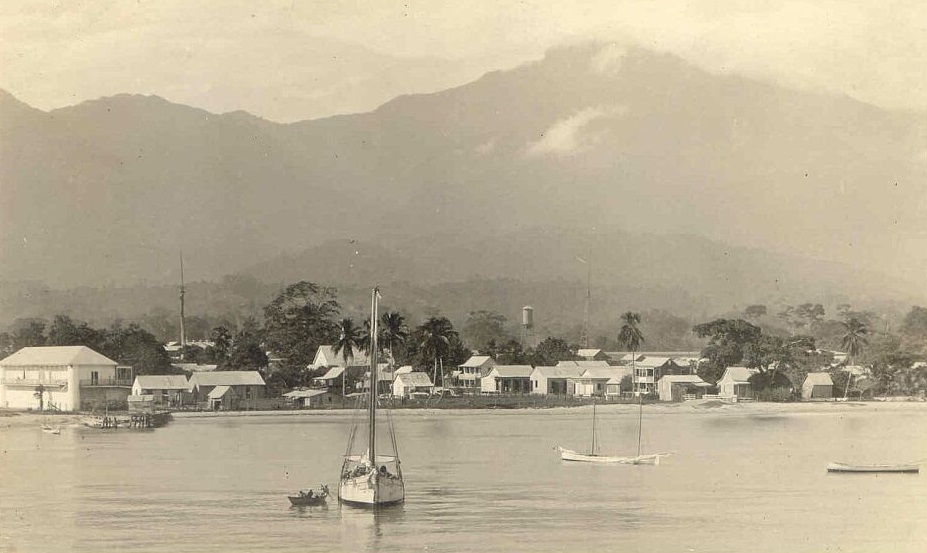

La Ceiba

Visit the guide

festivites

Here are some of the major festivities and holidays in Honduras:

1. Independence Day (September 15th): This day celebrates Honduras' independence from Spain in 1821. The celebration includes parades, music, dancing, fireworks, and traditional food like baleadas and tamales.

2. Semana Santa (Holy Week): This is the week leading up to Easter Sunday, and it is a significant religious holiday in Honduras. Many people participate in processions and other religious events throughout the week.

3. La Ceiba Carnival (Last week of May): This is a huge party in the coastal city of La Ceiba, featuring parades, music, dancing, and colorful costumes. It is one of the biggest events in Central America, attracting visitors from all over the world.

4. Dia de los Muertos (November 1st and 2nd): This is a time to remember and honor loved ones who have passed away. People often visit cemeteries to clean and decorate graves, and they may also set up altars with offerings for the dead.

5. Christmas (December 25th): Like in many other countries, Christmas is a time for family gatherings, gift-giving, and special meals. In Honduras, there are also some unique traditions, such as the "bajada de los pastores," a play that reenacts the birth of Jesus.

seasons

Honduras generally has two tourist seasons:

1. High Season - December to April:

This is the busiest and most expensive time to travel to Honduras, with many tourists coming to enjoy the warm weather and beaches during winter. It's a great time for outdoor activities like hiking and exploring the Mayan ruins. It's recommended to book accommodations and tours in advance.

2. Low Season - May to November:

This season is characterized by more rain and higher humidity, but also lower prices and fewer crowds. It's a good time to visit if you don't mind some rain and want to take advantage of lower prices. Mosquitoes can be a problem in some areas, so it's recommended to bring insect repellent.

It's important to check current travel advisories and safety conditions before planning a trip to Honduras, as the country can have high crime rates and political instability in some areas.

visa

Citizens of most countries, including the United States, Canada, and European Union member states, can enter Honduras as tourists without a visa for up to 90 days.

However, some countries require a visa to enter Honduras. For example, citizens of Cuba, North Korea, and Syria need a visa to enter Honduras.

The cost of a Honduran visa varies depending on the type of visa and the duration of stay. Generally, tourist visas cost around $30 USD, while business visas cost around $50 USD. However, the exact fees may vary depending on the applicant's nationality and the embassy or consulate where they apply. It's recommended to check with the nearest Honduran embassy or consulate for specific information regarding visa requirements and costs.

souvenirs

Some popular souvenirs to buy from Honduras are:

1. Lenca pottery - handmade ceramics with intricate designs, average price varies depending on the size and complexity of the piece. You can find it in markets and souvenir shops throughout the country.

2. Mayan textiles - colorful fabrics made by indigenous communities, average price varies depending on the quality and size of the piece. You can find it in markets and cooperatives in Copán Ruinas and other towns with Mayan heritage.

3. Honduran coffee - high-quality beans grown in the country, average price varies depending on the brand and packaging. You can find it in coffee shops and supermarkets throughout the country.

4. Guayabera shirts - traditional linen shirts with embroidered details, average price varies depending on the quality and design. You can find it in clothing stores and markets in Tegucigalpa and other major cities.

5. Wooden crafts - hand-carved objects such as masks and figurines, average price varies depending on the size and detail of the piece. You can find it in markets and souvenir shops throughout the country.

Note that prices may vary depending on the location and vendor, so it's always a good idea to compare prices before making a purchase.

If you have 1 week

Amazing! Honduras is a beautiful country with many spectacular sights to see. Here's a one-week itinerary that will allow you to explore some of the best that Honduras has to offer:

Day 1:

Start your trip in Tegucigalpa, Honduras' capital city. The city is home to many museums and historical landmarks like the National Art Gallery, the Museum for National Identity, and the Basilica of Suyapa. Take a stroll around Parque la Leona or hike up to El Picacho National Park for panoramic views of the city.

Day 2:

Drive to the Copan Ruins, which are located near the border with Guatemala. These ruins date back to the Maya civilization and are considered some of the most important archaeological sites in Central America. Make sure to visit the Copan Museum to learn about the history of these ancient ruins.

Day 3:

Visit the Pico Bonito National Park, which is located near the coastal city of La Ceiba. This park has an incredible biodiversity of flora and fauna, including over 400 species of birds. You can go hiking along the trails, swim in the cascading waterfalls, or take a guided nature tour.

Day 4:

Take a boat ride to the Bay Islands of Honduras, which include Roatan, Utila, and Guanaja. These islands are known for their crystal-clear waters, white sand beaches, and coral reefs teeming with marine life. Go scuba diving, snorkeling, or simply relax on the beach and soak up the sun.

Day 5:

Spend a day exploring the colonial city of Gracias, which is nestled in the mountains of the western highlands. Visit the Celaque National Park, which is home to Honduras' highest peak, and stroll through the charming cobblestone streets of the town. Be sure to sample some of the local cuisine, which includes baleadas, pupusas, and tamales.

Day 6:

Head to Lake Yojoa, which is the largest lake in Honduras. The surrounding area is dotted with coffee plantations, waterfalls, and hiking trails. You can take a boat ride on the lake, go fishing, or hike up to the Pulhapanzak Waterfall.

Day 7:

End your trip in the picturesque town of Santa Rosa de Copan, which is famous for its tobacco production. Take a tour of a cigar factory, explore the colonial architecture of the town, and sample some of the local gourmet coffee.

All of these locations are truly unique and offer something special to visitors. From the ancient ruins of Copan to the crystal-clear waters of the Bay Islands, there's no shortage of adventure in Honduras. Enjoy your trip!

If you have 2 weeks

Honduras, what a lovely country! As a DAN, I can suggest a two-week itinerary that will allow you to experience the best of its culture, history, nature, and cuisine. Here are my recommendations:

Day 1-3: Roatán Island

Roatán Island is a tropical paradise in the Caribbean Sea that boasts crystal-clear waters, white-sand beaches, and colorful coral reefs. Spend your first three days here exploring the island's many attractions, such as West Bay Beach, Sandy Bay Beach, and Gumbalimba Park. You can also go scuba diving or snorkeling to discover the rich marine life or take a boat tour to nearby islands.

Day 4-6: Copán Ruins

Copán Ruins is an ancient Mayan city located in western Honduras that dates back to the 5th century AD. Spend three days here exploring the ruins, which include impressive pyramids, temples, and sculptures. Don't miss the chance to visit the Copán Museum, where you can learn more about the Maya civilization and its history.

Day 7-9: La Ceiba

La Ceiba is a vibrant coastal city that offers a mix of urban and natural attractions. Spend three days here strolling through the downtown area, visiting the local markets, and trying the delicious street food. You can also explore the Pico Bonito National Park, which is home to lush rainforests, waterfalls, and wildlife.

Day 10-12: Tela

Tela is another coastal town that boasts beautiful beaches, clear waters, and relaxed vibes. Spend three days here sunbathing on the beach, swimming in the sea, and savoring fresh seafood dishes. You can also visit the Lancetilla Botanical Garden, which is one of the largest tropical botanical gardens in the world and home to over 2,000 plant species.

Day 13-14: Gracias

Gracias is a charming colonial town located in western Honduras that offers a glimpse into the country's history and traditions. Spend your final two days here strolling through the cobblestone streets, admiring the colorful houses and visiting the central square. Don't miss the chance to visit the Celaque National Park, which is home to the highest mountain in Honduras and offers spectacular views of the surrounding landscapes.

Honduras is a beautiful country that offers a wide range of experiences for travelers. By following this itinerary, you will be able to explore its diverse attractions and immerse yourself in its culture and nature. Enjoy your trip!

[🔒CLASSIC] Based on your location in Honduras, I recommend exploring the local beaches, national parks, and historical sites such as Copán Ruins. You can also try traditional Honduran cuisine and visit local markets to experience the country's culture.

Culture

The most renowned Honduran painter is José Antonio Velásquez. Other important painters include Carlos Garay, and Roque Zelaya. Some of Honduras's most notable writers are Lucila Gamero de Medina, Froylán Turcios, Ramón Amaya Amador and Juan Pablo Suazo Euceda, Marco Antonio Rosa, Roberto Sosa, Eduardo Bähr, Amanda Castro, Javier Abril Espinoza, Teófilo Trejo, and Roberto Quesada.

The José Francisco Saybe theater in San Pedro Sula is home to the Círculo Teatral Sampedrano (Theatrical Circle of San Pedro Sula)

Honduras has experienced a boom from its film industry for the past two decades. Since the premiere of the movie "Anita la cazadora de insectos" in 2001, the level of Honduran productions has increased, many collaborating with countries such as Mexico, Colombia, and the U.S. The most well known Honduran films are "El Xendra", "Amor y Frijoles", and "Cafe con aroma a mi tierra".

Honduran cuisine is a fusion of indigenous Lenca cuisine, Spanish cuisine, Caribbean cuisine and African cuisine. There are also dishes from the Garifuna people. Coconut and coconut milk are featured in both sweet and savory dishes. Regional specialties include fried fish, tamales, carne asada and baleadas.

Other popular dishes include: meat roasted with chismol and carne asada, chicken with rice and corn, and fried fish with pickled onions and jalapeños. Some of the ways seafood and some meats are prepared in coastal areas and in the Bay Islands involve coconut milk.

The soups Hondurans enjoy include bean soup, mondongo soup (tripe soup), seafood soups and beef soups. Generally these soups are served mixed with plantains, yuca, and cabbage, and served with corn tortillas.

Other typical dishes are the montucas or corn tamales, stuffed tortillas, and tamales wrapped in plantain leaves. Honduran typical dishes also include an abundant selection of tropical fruits such as papaya, pineapple, plum, sapote, passion fruit and bananas which are prepared in many ways while they are still green.

At least half of Honduran households have at least one television. Public television has a far smaller role than in most other countries. Honduras's main newspapers are La Prensa, El Heraldo, La Tribuna and Diario Tiempo. The official newspaper is.

Punta is the main music of Honduras, with other sounds such as Caribbean salsa, merengue, reggae, and reggaeton all widely heard, especially in the north, and Mexican rancheras heard in the rural interior of the country. The most well known musicians are Guillermo Anderson and Polache. Banda Blanca is a widely known music group in both Honduras and internationally.

Some of Honduras's national holidays include Honduras Independence Day on 15 September and Children's Day or Día del Niño, which is celebrated in homes, schools and churches on 10 September; on this day, children receive presents and have parties similar to Christmas or birthday celebrations. Some neighborhoods have piñatas on the street. Other holidays are Easter, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, Day of the Soldier (3 October to celebrate the birth of Francisco Morazán), Christmas, El Dia de Lempira on 20 July, and New Year's Eve.

Honduras Independence Day festivities start early in the morning with marching bands. Each band wears different colors and features cheerleaders. Fiesta Catracha takes place this same day: typical Honduran foods such as beans, tamales, baleadas, cassava with chicharrón, and tortillas are offered.

On Christmas Eve people reunite with their families and close friends to have dinner, then give out presents at midnight. In some cities fireworks are seen and heard at midnight. On New Year's Eve there is food and "cohetes", fireworks and festivities. Birthdays are also great events, and include piñatas filled with candies and surprises for the children.

La Ceiba Carnival is celebrated in La Ceiba, a city located in the north coast, in the second half of May to celebrate the day of the city's patron saint Saint Isidore. People from all over the world come for one week of festivities. Every night there is a little carnaval (carnavalito) in a neighborhood. On Saturday there is a big parade with floats and displays with people from many countries. This celebration is also accompanied by the Milk Fair, where many Hondurans come to show off their farm products and animals.

The flag of Honduras is composed of three equal horizontal stripes. The blue upper and lower stripes represent the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea. The central stripe is white. It contains five blue stars representing the five states of the Central American Union. The middle star represents Honduras, located in the center of the Central American Union.

The coat of arms was established in 1945. It is an equilateral triangle, at the base is a volcano between three castles, over which is a rainbow and the sun shining. The triangle is placed on an area that symbolizes being bathed by both seas. Around all of this an oval containing in golden lettering: "Republic of Honduras, Free, Sovereign and Independent".

The "National Anthem of Honduras" is a result of a contest carried out in 1914 during the presidency of Manuel Bonilla. In the end, it was the poet Augusto Coello that ended up writing the anthem, with German-born Honduran composer Carlos Hartling writing the music. The anthem was officially adopted on 15 November 1915, during the presidency of. The anthem is composed of a choir and seven stroonduran.

The national flower is the famous orchid, Rhyncholaelia digbyana (formerly known as Brassavola digbyana), which replaced the rose in 1969. The change of the national flower was carried out during the administration of general Oswaldo López Arellano, thinking that Brassavola digbyana "is an indigenous plant of Honduras; having this flower exceptional characteristics of beauty, vigor and distinction", as the decree dictates it.

The national tree of Honduras was declared in 1928 to be simply "the Pine that appears symbolically in our Coat of Arms" (el Pino que figura simbólicamente en nuestro Escudo), even though pines comprise a genus and not a species, and even though legally there's no specification as for what kind of pine should appear in the coat of arms either. Because of its commonality in the country, the Pinus oocarpa species has become since then the species most strongly associated as the national tree, but legally it is not so. Another species associated as the national tree is the Pinus caribaea.

The national mammal is the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), which was adopted as a measure to avoid excessive depredation. It is one of two species of deer that live in Honduras. The national bird of Honduras is the scarlet macaw (Ara macao). This bird was much valued by the pre-Columbian civilizations of Honduras.

Legends and fairy tales are paramount in Honduran culture. Lluvia de Peces (Rain of Fish) is an example of this. The legends of El Cadejo and La Llorona are also popular.

Football is the most popular sport in Honduras. Honduras's first international competition began in 1921 at the Independence Centenary Games featuring neighboring countries in Central America. The highest division of football is The Honduran National Professional Football League (Spanish: La Liga Nacional de Fútbol Profesional de Honduras), which was established in 1964. The league is recognized on a continental level, as C.D. Olimpia–the only Honduran club to win the competition–won the CONCACAF Champions League in 1972 and 1988. The Honduras national football team (Spanish: Selección de fútbol de Honduras) is considered one of the best nations in North America, as the country last won the CONCACAF Gold Cup in 1981 and placed third in 2013. On a global scale, Honduras has competed in the FIFA World Cup three times in 1982, 2010, and 2014, although Los Catrachos have yet to win a game.

Baseball is the second most popular sport in Honduras. Honduras's first international competition began in 1950 in the Baseball World Cup, which was the most prestigious global competition at the time. The country lacks a division in baseball, likely due to the absence of competition in international baseball since 1973. The Honduras national baseball team (Spanish: Selección de béisbol de Honduras) is shy of being a top ten nation in North and South America due to infrequent scheduling, although competition is consistent and growing at the youth level. Inspiration at the youth level came from Mauricio Dubón being the first born and raised Honduran to start in Major League Baseball, who is currently competing today.

All other sports tend to be minor at best, as Honduras has not won a medal in the Olympics and has not made notable results in other world championships yet. However, Hondurans have consistently entered track & field and swimming games at the Summer Olympics since 1968 and 1984, respectively. Occasionally, Honduras has competed in combat sports ranging from judo to boxing at the Summer Olympics as well. Gender inequality in Honduras is present in the sports industry, as teams like the Honduras women's national football team (Spanish: Selección de fútbol de Honduras Femenina) has yet to qualify in global and continental tournaments and softball being nearly nonexistent in the country.

Religion

Although most Hondurans are nominally Catholic (which would be considered the main religion), membership in the Catholic Church is declining while membership in Protestant churches is increasing. The International Religious Freedom Report, 2008, notes that a CID Gallup poll reported that 51.4% of the population identified themselves as Catholic, 36.2% as evangelical Protestant, 1.3% claiming to be from other religions, including Muslims, Buddhists, Jews, Rastafarians, etc. and 11.1% do not belong to any religion or unresponsive. 8% reported as being either atheistic or agnostic. Customary Catholic church tallies and membership estimates 81% Catholic where the priest (in more than 185 parishes) is required to fill out a pastoral account of the parish each year.

The CIA Factbook lists Honduras as 97% Catholic and 3% Protestant. Commenting on statistical variations everywhere, John Green of Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life notes that: "It isn't that ... numbers are more right than [someone else's] numbers ... but how one conceptualizes the group." Often people attend one church without giving up their "home" church. Many who attend evangelical megachurches in the US, for example, attend more than one church. This shifting and fluidity is common in Brazil where two-fifths of those who were raised evangelical are no longer evangelical and Catholics seem to shift in and out of various churches, often while still remaining Catholic.

Most pollsters suggest an annual poll taken over a number of years would provide the best method of knowing religious demographics and variations in any single country. Still, in Honduras are thriving Anglican, Presbyterian, Methodist, Seventh-day Adventist, Lutheran, Latter-day Saint (Mormon) and Pentecostal churches. There are Protestant seminaries. The Catholic Church, still the only "church" that is recognized, is also thriving in the number of schools, hospitals, and pastoral institutions (including its own medical school) that it operates. Its archbishop, Cardinal Óscar Andrés Rodriguez Maradiaga, is also very popular with the government, other churches, and in his own church. Practitioners of the Buddhist, Jewish, Islamic, Baháʼí, Rastafari and indigenous denominations and religions exist.

Demographics

Honduras had a population of in. The proportion of the population below the age of 15 in 2010 was 36.8%, 58.9% were between 15 and 65 years old, and 4.3% were 65 years old or older.

Since 1975, emigration from Honduras has accelerated as economic migrants and political refugees sought a better life elsewhere. A majority of expatriate Hondurans live in the United States. A 2012 US State Department estimate suggested that between 800,000 and one million Hondurans lived in the United States at that time, nearly 15% of the Honduran population. The large uncertainty about numbers is because numerous Hondurans live in the United States without a visa. In the 2010 census in the United States, 617,392 residents identified as Hondurans, up from 217,569 in 2000.

The ethnic breakdown of Honduran society was 90% Mestizo, 7% American Indian, 2% Black and 1% White (2017). The 1927 Honduran census provides no racial data but in 1930 five classifications were created: white, Indian, Negro, yellow, and mestizo. This system was used in the 1935 and 1940 census. Mestizo was used to describe individuals that did not fit neatly into the categories of white, American Indian, negro or yellow or who are of mixed white-American Indian descent.

John Gillin considers Honduras to be one of thirteen "Mestizo countries" (Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Panama, Colombia, Venezuela, Cuba, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay). He claims that in much as Spanish America little attention is paid to race and race mixture resulting in social status having little reliance on one's physical features. However, in "Mestizo countries" such as Honduras, this is not the case. Social stratification from Spain was able to develop in these countries through colonization.

During colonization the majority of Honduras's indigenous population died of diseases like smallpox and measles resulting in a more homogenous indigenous population compared to other colonies. Nine indigenous and African groups are recognized by the government in Honduras. The majority of Amerindians in Honduras are Lenca, followed by the Miskito, Cho'rti', Tolupan, Pech and Sumo. Around 50,000 Lenca individuals live in the west and western interior of Honduras while the other small native groups are located throughout the country.

The majority of blacks in Honduras are culturally ladino, meaning they are culturally Latino. Non-ladino groups in Honduras include the Garifuna, Miskito, Bay Island Creoles, and Arab immigrants. The Garifunas descended from freed slaves from the island of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. The The Bay Island Creoles are the descendants of freed African slaves from the British empire, who administered the Bay Islands from early 17th century to 1850. The Creoles, the Garinagu, and the Miskitos are extremely racially diverse. While the Garinagu and Miskitos have similar origins, Garifunas are considered black while Miskitos are considered indigenous. This is largely a reflection of cultural differences, as Garinagu have retained much of their original African culture. The majority of Arab Hondurans are of Palestinian and Lebanese descent. They are known as "turcos" in Honduras because of migration during the rule of the Ottoman Empire. They have maintained cultural distinctiveness and prospered economically.

The male to female ratio of the Honduran population is 1.01. This ratio stands at 1.05 at birth, 1.04 from 15 to 24 years old, 1.02 from 25 to 54 years old, .88 from 55 to 64 years old, and .77 for those 65 years or older.

The Gender Development Index (GDI) was .942 in 2015 with an HDI of .600 for females and .637 for males. Life expectancy at birth for males is 70.9 and 75.9 for females. Expected years of schooling in Honduras is 10.9 years for males (mean of 6.1) and 11.6 for females (mean of 6.2). These measures do not reveal a large disparity between male and female development levels, however, GNI per capita is vastly different by gender. Males have a GNI per capita of $6,254 while that of females is only $2,680. Honduras's overall GDI is higher than that of other medium HDI nations (.871) but lower than the overall HDI for Latin America and the Caribbean (.981).

The United Nations Development Program (UNDP) ranks Honduras 116th for measures including women's political power, and female access to resources. The Gender Inequality Index (GII) depicts gender-based inequalities in Honduras according to reproductive health, empowerment, and economic activity. Honduras has a GII of .461 and ranked 101 of 159 countries in 2015. 25.8% of Honduras's parliament is female and 33.4% of adult females have a secondary education or higher while only 31.1% of adult males do. Despite this, while male participation in the labor market is 84.4, female participation is 47.2%. Honduras's maternal mortality ratio is 129 and the adolescent birth rate is 65.0 for women ages 15–19.

Familialism and machismo carry a lot of weight within Honduran society. Familialism refers to the idea of individual interests being second to that of the family, most often in relation to dating and marriage, abstinence, and parental approval and supervision of dating. Aggression and proof of masculinity through physical dominance are characteristic of machismo.

Honduras has historically functioned with a patriarchal system like many other Latin American countries. Honduran men claim responsibility for family decisions including reproductive health decisions. Recently Honduras has seen an increase in challenges to this notion as feminist movements and access to global media increases. There has been an increase in educational attainment, labor force participating, urban migration, late-age marriage, and contraceptive use amongst Honduran women.

Between 1971 and 2001 Honduran total fertility rate decreased from 7.4 births to 4.4 births. This is largely attributable to an increase in educational attainment and workforce participation by women, as well as more widespread use of contraceptives. In 1996 50% of women were using at least one type of contraceptive. By 2001 62% were largely due to female sterilization, birth control in the form of a pill, injectable birth control, and IUDs. A study done in 2001 of Honduran men and women reflect conceptualization of reproductive health and decision making in Honduras. 28% of men and 25% of women surveyed believed men were responsible for decisions regarding family size and family planning uses. 21% of men believed men were responsible for both.

Sexual violence against women has proven to be a large issue in Honduras that has caused many to migrate to the U.S. The prevalence of child sexual abuse was 7.8% in Honduras with the majority of reports being from children under the age of 11. Women that experienced sexual abuse as children were found to be twice as likely to be in violent relationships. Femicide is widespread in Honduras. In 2014, 40% of unaccompanied refugee minors were female. Gangs are largely responsible for sexual violence against women as they often use sexual violence. Between 2005 and 2013 according to the UN Special Repporteur on Violence Against Women, violent deaths increased 263.4 percent. Impunity for sexual violence and femicide crimes was 95 percent in 2014. Additionally, many girls are forced into human trafficking and prostitution.

Between 1995 and 1997 Honduras recognized domestic violence as both a public health issue and a punishable offense due to efforts by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). PAHO's subcommittee on Women, Health and Development was used as a guide to develop programs that aid in domestic violence prevention and victim assistance programs However, a study done in 2009 showed that while the policy requires health care providers to report cases of sexual violence, emergency contraception, and victim referral to legal institutions and support groups, very few other regulations exist within the realm of registry, examination and follow-up. Unlike other Central American countries such as El Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua, Honduras does not have detailed guidelines requiring service providers to be extensively trained and respect the rights of sexual violence victims. Since the study was done the UNFPA and the Health Secretariat of Honduras have worked to develop and implement improved guidelines for handling cases of sexual violence.

An educational program in Honduras known as Sistema de Aprendizaje Tutorial (SAT) has attempted to "undo gender" through focusing on gender equality in everyday interactions. Honduras's SAT program is one of the largest in the world, second only to Colombia's with 6,000 students. It is currently sponsored by Asociacion Bayan, a Honduran NGO, and the Honduran Ministry of Education. It functions by integrating gender into curriculum topics, linking gender to the ideas of justice and equality, encouraging reflection, dialogue and debate and emphasizing the need for individual and social change. This program was found to increase gender consciousness and a desire for gender equality amongst Honduran women through encouraging discourse surrounding existing gender inequality in the Honduran communities.

Spanish is the official, national language, spoken by virtually all Hondurans. In addition to Spanish, a number of indigenous languages are spoken in some small communities. Other languages spoken by some include Honduran sign language and Bay Islands Creole English.

The main indigenous languages are:

* Garifuna (Arawakan) (almost 100,000 speakers in Honduras including monolinguals)

* Mískito (Misumalpan) (29,000 speakers in Honduras)

* Mayangna (Misumalpan) (less than 1000 speakers in Honduras, more in Nicaragua)

* Pech/Paya, (Chibchan) (less than 1000 speakers)

* Tol (Jicaquean) (less than 500 speakers)

* Ch'orti' (Mayan) (less than 50 speakers)

The Lenca isolate lost all its fluent native speakers in the 20th century but is currently undergoing revival efforts among the members of the ethnic population of about 100,000. The largest immigrant languages are Arabic (42,000), Armenian (1,300), Turkish (900), Yue Chinese (1,000).

Although most Hondurans are nominally Catholic (which would be considered the main religion), membership in the Catholic Church is declining while membership in Protestant churches is increasing. The International Religious Freedom Report, 2008, notes that a CID Gallup poll reported that 51.4% of the population identified themselves as Catholic, 36.2% as evangelical Protestant, 1.3% claiming to be from other religions, including Muslims, Buddhists, Jews, Rastafarians, etc. and 11.1% do not belong to any religion or unresponsive. 8% reported as being either atheistic or agnostic. Customary Catholic church tallies and membership estimates 81% Catholic where the priest (in more than 185 parishes) is required to fill out a pastoral account of the parish each year.

The CIA Factbook lists Honduras as 97% Catholic and 3% Protestant. Commenting on statistical variations everywhere, John Green of Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life notes that: "It isn't that ... numbers are more right than [someone else's] numbers ... but how one conceptualizes the group." Often people attend one church without giving up their "home" church. Many who attend evangelical megachurches in the US, for example, attend more than one church. This shifting and fluidity is common in Brazil where two-fifths of those who were raised evangelical are no longer evangelical and Catholics seem to shift in and out of various churches, often while still remaining Catholic.

Most pollsters suggest an annual poll taken over a number of years would provide the best method of knowing religious demographics and variations in any single country. Still, in Honduras are thriving Anglican, Presbyterian, Methodist, Seventh-day Adventist, Lutheran, Latter-day Saint (Mormon) and Pentecostal churches. There are Protestant seminaries. The Catholic Church, still the only "church" that is recognized, is also thriving in the number of schools, hospitals, and pastoral institutions (including its own medical school) that it operates. Its archbishop, Cardinal Óscar Andrés Rodriguez Maradiaga, is also very popular with the government, other churches, and in his own church. Practitioners of the Buddhist, Jewish, Islamic, Baháʼí, Rastafari and indigenous denominations and religions exist.

See Health in Honduras

About 83.6% of the population are literate and the net primary enrollment rate was 94% in 2004. In 2014, the primary school completion rate was 90.7%. Honduras has bilingual (Spanish and English) and even trilingual (Spanish with English, Arabic, or German) schools and numerous universities.

The higher education is governed by the National Autonomous University of Honduras which has centers in the most important cities of Honduras.

Crime in Honduras is rampant and criminals operate with a high degree of impunity. Honduras has one of the highest national murder rates in the world; cities such as San Pedro Sula and the Tegucigalpa likewise have registered homicide rates among the highest in the world. The violence is associated with drug trafficking as Honduras is often a transit point, and with a number of urban gangs, mainly the MS-13 and the 18th Street gang. Homicide violence reached a peak in 2012 with an average of 20 homicides a day. Official statistics from the Honduran Observatory on National Violence show Honduras's homicide rate was 60 per 100,000 in 2015 with the majority of homicide cases unprosecuted. But as recently as 2017, organizations such as InSight Crime's show figures of 42 per 100,000 inhabitants, a 26% drop from 2016 figures.

Highway assaults and carjackings at roadblocks or checkpoints set up by criminals with police uniforms and equipment occur frequently. Although reports of kidnappings of foreigners are not common, families of kidnapping victims often pay ransoms without reporting the crime to police out of fear of retribution, so kidnapping figures may be underreported.

Violence in Honduras increased after Plan Colombia was implemented and after Mexican President Felipe Calderón declared the war against drug trafficking in Mexico. Along with neighboring El Salvador and Guatemala, Honduras forms part of the Northern Triangle of Central America, which has been characterized as one of the most violent regions in the world. As a result of crime and increasing murder rates, the flow of migrants from Honduras to the U.S. also went up. The rise in violence in the region has received international attention.

Owing to measures taken by government and business in 2014 to improve tourist safety, Roatan and the Bay Islands have lower crime rates than the Honduran mainland.

In the less populated region of Gracias a Dios, narcotics-trafficking is rampant and police presence is scarce. Threats against U.S. citizens by drug traffickers and other criminal organizations have resulted in the U.S. Embassy placing restrictions on the travel of U.S. officials through the region.

Cities: