Acapulco de Juárez

Visit the guide

Aguascalientes

Visit the guide

Cancún

Visit the guide

Chihuahua

Visit the guide

Ciudad Juárez

Visit the guide

Culiacán Rosales

Visit the guide

Ecatepec de Morelos

Visit the guide

Guadalajara

Visit the guide

Guadalupe

Visit the guide

Hermosillo

Visit the guide

León

Visit the guide

Mexicali

Visit the guide

Mexico City

Visit the guide

Monterrey

Visit the guide

Morelia

Visit the guide

Mérida

Visit the guide

Naucalpan de Juárez

Visit the guide

Nezahualcóyotl

Visit the guide

Puebla

Visit the guide

Querétaro

Visit the guide

Reynosa

Visit the guide

Saltillo

Visit the guide

San Luis Potosí

Visit the guide

Tijuana

Visit the guide

Tlalnepantla de Baz

Visit the guide

Tlaquepaque

Visit the guide

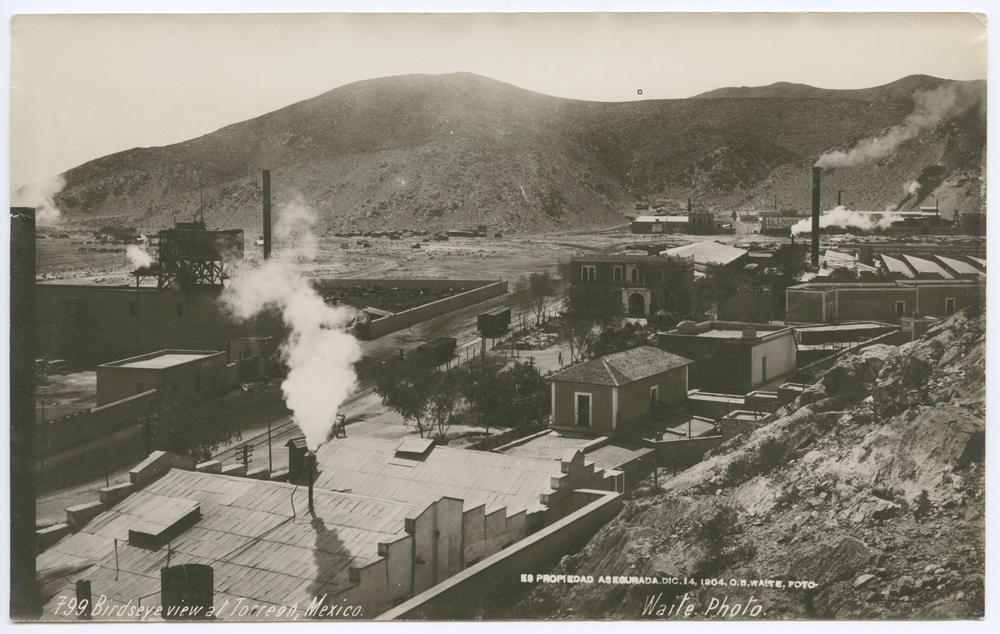

Torreón

Visit the guide

Tuxtla Gutiérrez

Visit the guide

Victoria de Durango.

Visit the guide

Zapopan

Visit the guide

festivites

1. Dia de los Muertos (Day of the Dead): Celebrated on November 1st and 2nd, this holiday is a time to honor and remember loved ones who have passed away. Altars are set up with offerings such as flowers, candles, food, and drinks for the deceased, and people often dress up in colorful costumes and paint their faces in intricate designs.

2. Cinco de Mayo: This holiday commemorates the Mexican army's victory over the French at the Battle of Puebla on May 5, 1862. While it is not a major holiday in Mexico, it is widely celebrated in the United States as a day to celebrate Mexican culture and heritage.

3. Navidad (Christmas): Christmas is a major holiday in Mexico, with celebrations starting on December 12th (Dia de la Virgen de Guadalupe) and continuing until January 6th (Dia de los Reyes Magos). Families gather to celebrate with traditional foods like tamales and ponche, and children receive gifts from the Three Wise Men on January 6th.

4. Semana Santa (Holy Week): Celebrated during the week leading up to Easter, Semana Santa is a time of religious observance and reflection. Many Mexicans participate in processions and reenactments of the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

5. Independence Day: Celebrated on September 16th, Independence Day commemorates the start of the Mexican War of Independence in 1810. Festivities include parades, fireworks, and the ringing of the bell of El Grito, a cry for independence made by Miguel Hidalgo, one of the leaders of the war.

seasons

Mexico has three main tourist seasons:

1. High Season: From December to April, this is the busiest time for tourism in Mexico, especially in coastal destinations. The weather is generally dry and sunny, making it ideal for activities such as swimming and sunbathing. It is advisable to book accommodations and tours in advance during this period due to high demand.

2. Shoulder Season: From May to August, this season falls between the high and low seasons. The weather can be quite hot and humid, but it's also when you can find some great deals on accommodations and travel packages. This is a good time to explore Mexico's interior regions and avoid the crowds at the popular beach destinations.

3. Low Season: From September to November, this is the least busy time for tourism in Mexico. The weather can be unpredictable, with occasional hurricanes and heavy rains, but it can also be a great time to visit if you're looking for lower prices and fewer crowds. Some attractions may close for maintenance or renovation during this period, so it's best to check ahead of time before planning your trip.

visa

Here are some special visa rules for citizens of certain countries who want to visit Mexico:

1. Visa not required: Citizens of over 60 countries, including the United States, Canada, and most European nations, do not need a visa to enter Mexico for tourism or business purposes for stays up to 180 days.

2. Electronic Travel Authorization (Autorización Electrónica de Viaje or "AVE"): Citizens of Turkey, Ukraine, and Georgia must obtain an AVE online before traveling to Mexico. The cost of the AVE is approximately $20 USD.

3. Visitor Visa: Citizens of certain countries, such as China, India, and Russia, must obtain a visitor visa from a Mexican embassy or consulate before traveling to Mexico. The cost of the visitor visa is approximately $36 USD.

4. Transit Visa: Citizens of some countries, such as Cuba and Afghanistan, may need a transit visa if they are passing through Mexico on their way to another destination. The cost of the transit visa is approximately $23 USD.

The costs listed here are approximate and may vary depending on the country of origin and the specific circumstances of the traveler's visit. It is recommended to check with the nearest Mexican embassy or consulate for the latest information on visa requirements and costs.

souvenirs

Some of the best souvenirs to buy from Mexico include:

1. Handcrafted pottery - Prices range from $10 to $100 depending on size and intricacy. You can find them at markets like Mercado de Artesanías La Ciudadela in Mexico City.

2. Silver Jewelry - Prices vary depending on the piece and quality, but you can find beautiful silver bracelets, earrings, and necklaces for around $20 to $50. Stores like Casa de las Artesanías in Taxco are known for their selection of quality silver jewelry.

3. Traditional Mexican clothing - Prices range from $20 to $150 depending on the garment. You can find a variety of items like embroidered blouses, dresses, and huipiles (traditional blouses) in markets such as Mercado de San Juan in Mexico City.

4. Talavera pottery - Prices vary depending on the item and size, but you can find plates, bowls, and other decorative pieces for around $10 to $50. Puebla is famous for its Talavera pottery, and you can find it in stores like Uriarte Talavera and Talavera de la Reyna.

5. Tequila - Prices vary depending on brand and quality, but you can find good bottles of tequila starting at $20 to $30. You can find them in specialized stores such as La Europea or La Naval in Mexico City.

Remember that prices may vary depending on the region or store you visit, and bargaining is sometimes possible in markets.

If you have 1 week

Great to hear that you are in Mexico! Here is a one-week itinerary suggestion for you:

Day 1: Start your day by visiting the ruins of Teotihuacan, located just outside of Mexico City. This ancient city was once the largest in pre-Columbian America and features impressive pyramids, temples, and murals. After exploring the site, head back to Mexico City and visit El Zócalo, one of the largest public squares in the world, home to the Metropolitan Cathedral and the National Palace.

Day 2: Take a day trip to Xochimilco, known for its canals and colorful boats called trajineras. Rent a trajinera for a serene ride through the waterways while enjoying traditional Mexican food and drink from vendors on other boats.

Day 3: Make your way to Guadalajara, the capital of Jalisco state. Visit the historic center and enjoy the colonial architecture, including the Hospicio Cabañas, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Day 4: Travel to Puerto Vallarta, a popular beach destination on Mexico's Pacific coast. Relax on the beach or take a stroll along the Malecón boardwalk, which offers stunning views of the ocean and the iconic Los Arcos rock formations.

Day 5: Explore the Yucatan Peninsula and visit Chichen Itza, one of the most famous Mayan archaeological sites in Mexico. Admire the impressive structures, such as the Kukulkan Pyramid, and learn about the history and culture of the Mayan civilization.

Day 6: Head to Tulum, a coastal town located on the Caribbean Sea. Visit the Tulum Ruins, an ancient Mayan walled city overlooking the turquoise waters. Spend the rest of the day lounging on the beach or exploring the nearby cenotes, natural swimming holes unique to the region.

Day 7: Return to Mexico City and visit the Frida Kahlo Museum, also known as the Blue House. This was the home of the famous Mexican artist and is now a museum showcasing her life and work. End your day with a stroll through the trendy neighborhood of Roma, known for its vibrant street art, boutiques, and restaurants.

I hope you enjoy this itinerary! These destinations offer a mix of history, culture, nature, and relaxation, showcasing some of the best that Mexico has to offer.

If you have 2 weeks

Wonderful! Mexico is a beautiful country with so much to offer. Here's a two week itinerary that will allow you to experience some of the best that Mexico has to offer:

Week 1:

Day 1-2: Begin your trip in Mexico City, the bustling capital of Mexico. Start by exploring the historical center, which is home to stunning architecture such as the Palacio de Bellas Artes and the Metropolitan Cathedral. Make sure to also visit the Templo Mayor, an important Aztec temple that was discovered in the heart of the city.

Day 3-4: Next, head to Oaxaca, a charming colonial town known for its vibrant culture and delicious food. Spend a day exploring the colorful markets, sampling local delicacies like mole and chapulines (roasted grasshoppers), and visiting the ancient ruins of Monte Alban.

Day 5-7: From Oaxaca, make your way to Puerto Escondido, a laid-back beach town on the Pacific coast. There, you can soak up the sun, swim in the turquoise waters, and take surf lessons at one of the many excellent surf breaks. Don't miss the opportunity to witness bioluminescence at night during a lagoon kayak tour.

Week 2:

Day 8-10: On your seventh day, head to San Cristobal de las Casas, a charming colonial town located in the highlands of Chiapas. Take a guided tour to Sumidero Canyon, where you can see breathtaking views of the gorge and spot some local wildlife.

Day 11-12: Continue your adventure with a trip to Palenque, an ancient Maya city that dates back to 226 BC. Explore the archaeological site and marvel at the impressive structures and intricate carvings.

Day 13-14: Finally, end your trip in Tulum, a stunning beach town on the Caribbean coast. Visit the Tulum ruins, a well-preserved ancient Maya coastal trading port, and then relax on the beach or go snorkeling in the crystal clear waters of the cenotes.

This itinerary allows you to experience the diversity of Mexico's landscapes, from the bustling cities to the laid-back beaches, as well as learn about the country's rich history and culture. Every destination has its unique charm and beauty that is worth exploring, and I believe this trip will create everlasting memories for you.

Culture

Mexican culture reflects the complexity of the country's history through the blending of indigenous cultures and the culture of Spain during Spain's 300-year colonial rule of Mexico. The Porfirian era (el Porfiriato) (1876–1911), was marked by economic progress and peace. After four decades of civil unrest and war, Mexico saw the development of philosophy and the arts, promoted by President Porfirio Díaz himself. Since that time, as accentuated during the Mexican Revolution, cultural identity has had its foundation in the mestizaje, of which the indigenous (i.e. Amerindian) element is the core. In light of the various ethnicities that formed the Mexican people, José Vasconcelos in La Raza Cósmica (The Cosmic Race) (1925) defined Mexico to be the melting pot of all races (thus extending the definition of the mestizo) not only biologically but culturally as well. Other Mexican intellectuals grappled with the idea of Lo Mexicano, which seeks "to discover the national ethos of Mexican culture." Nobel laureate Octavio Paz explores the notion of a Mexican national character in The Labyrinth of Solitude.

Painting is one of the oldest arts in Mexico. Cave painting in Mexican territory is about 7500 years old and has been found in the caves of the Baja California Peninsula. Pre-Columbian Mexico is present in buildings and caves, in Aztec codices, in ceramics, in garments, etc.; examples of this are the Maya mural paintings of Bonampak, or those of Teotihuacán, those of Cacaxtla and those of Monte Albán. Mural painting with Christian religious themes had an important flowering during the 16th century, early colonial era in newly constructed churches and monasteries. Examples can be found in Acolman, Actopan, Huejotzingo, Tecamachalco and Zinacantepec.

As with most art during the early modern era in the West, colonial-era Mexican art was religious during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Starting in the late seventeenth century, and, most prominently in the eighteenth century, secular portraits and images of racial types, so-called casta painting appeared. Important painters of the late colonial period were Juan Correa, Cristóbal de Villalpando and Miguel Cabrera. In early post-independence Mexico, Nineteenth-century painting had a marked romantic influence; landscapes and portraits were the greatest expressions of this era. Hermenegildo Bustos is one of the most appreciated painters of the historiography of Mexican art. Other painters include Santiago Rebull, Félix Parra, Eugenio Landesio, and his noted pupil, the landscape artist José María Velasco.

In the 20th century has achieved world renown with painters such as Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco, the so-called "Big Three" of Mexican muralism. They were commissioned by the Mexican government to paint large-scale historical murals on the walls of public buildings, which helped shape popular perceptions of the Mexican Revolution and Mexican cultural identity. Frida Kahlo's largely personal portraiture has gained enormous popularity.

In the 19th century the neoclassical movement arose as a response to the objectives of the republican nation, one of its examples are the Hospicio Cabañas where the strict plastic of the classical orders are represented in their architectural elements, new religious buildings also arise, civilian and military that demonstrate the presence of neoclassicism. Romanticists from a past seen through archeology show images of medieval Europe, Islamic and pre-Columbian Mexico in the form of architectural elements in the construction of international exhibition pavilions looking for an identity typical of the national culture. The art nouveau, and the art deco were styles introduced into the design of the Palacio de Bellas Artes to mark the identity of the Mexican nation with Greek-Roman and pre-Columbian symbols.

The emergence of the new Mexican architecture was born as a formal order of the policies of a nationalist state that sought modernity and the differentiation of other nations. The development of a Mexican modernist architecture was perhaps mostly fully manifested in the mid-1950s construction of the Ciudad Universitaria, Mexico City, the main campus of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Designed by the most prestigious architects of the era, including Mario Pani, Eugenio Peschard, and Enrique del Moral, the buildings feature murals by artists Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Chávez Morado. It has since been recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Juan O'Gorman was one of the first environmental architects in Mexico, developing the "organic" theory, trying to integrate the building with the landscape within the same approaches of Frank Lloyd Wright. In the search for a new architecture that does not resemble the styles of the past, it achieves a joint manifestation with the mural painting and the landscaping. Luis Barragán combined the shape of the space with forms of rural vernacular architecture of Mexico and Mediterranean countries (Spain-Morocco), integrating color that handles light and shade in different tones and opens a look at the international minimalism. He won the 1980 Pritzker Prize, the highest award in architecture.

The origin of the current Mexican cuisine was established during the Spanish colonial era, a mixture of the foods of Spain with native indigenous ingredients. Foods indigenous to Mexico include corn, pepper vegetables, calabazas, avocados, sweet potato, turkey, many beans, and other fruits and spices. Similarly, some cooking techniques used today are inherited from pre-Columbian peoples, such as the nixtamalization of corn, the cooking of food in ovens at ground level, grinding in molcajete and metate. With the Spaniards came the pork, beef and chicken meats; peppercorn, sugar, milk and all its derivatives, wheat and rice, citrus fruits and another constellation of ingredients that are part of the daily diet of Mexicans.

From this meeting of millennia old two culinary traditions, were born pozole, mole sauce, barbacoa and tamale is in its current forms, the chocolate, a large range of breads, tacos, and the broad repertoire of Mexican street foods. Beverages such as atole, champurrado, milk chocolate and aguas frescas were born; desserts such as acitrón and the full range of crystallized sweets, rompope, cajeta, jericaya and the wide repertoire of delights created in the convents of nuns in all parts of the country.

In 2005, Mexico presented the candidature of its gastronomy for World Heritage Site of UNESCO, the first time a country had presented its gastronomic tradition for this purpose. The result was negative, because the committee did not place the proper emphasis on the importance of corn in Mexican cuisine. On 16 November 2010 Mexican gastronomy was recognized as Intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO. In addition, Daniela Soto-Innes was named the best female chef in the world by The World's Best 50 Restaurants in April 2019.

Mexican literature has its antecedents in the literature of the indigenous settlements of Mesoamerica. Poetry had a rich cultural tradition in pre-Columbian Mexico, being divided into two broad categories—secular and religious. Aztec poetry was sung, chanted, or spoken, often to the accompaniment of a drum or a harp. While Tenochtitlan was the political capital, Texcoco was the cultural center; the Texcocan language was considered the most melodious and refined. The best well-known pre-Columbian poet is Nezahualcoyotl.

There are historical chronicles of the conquest of Mexico by participants, and, later, by historians. Bernal Díaz del Castillo's True History of the Conquest of the New Spain is still widely read today. Spanish-born poet Bernardo de Balbuena extolled the virtues of Mexico in Grandeza mexicana (Mexican grandeur) (1604). Baroque literature flourished in the 17th century; the most notable writers of this period were Juan Ruiz de Alarcón and Juana Inés de la Cruz. Sor Juana was famous in her own time, called the "Ten Muse."

The late colonial-era novel by José Joaquín Fernández de Lizardi, whose The Mangy Parrot ("El Periquillo Sarniento"), is said to be the first Latin American novel. Nineteenth-century liberal of Nahua origin Ignacio Manuel Altamirano is an important writer of the era, along with Vicente Riva Palacio, the grandson of Mexican hero of independence Vicente Guerrero, who authored a series of historical novels as well as poetry. In the modern era, the novel of the Mexican Revolution by Mariano Azuela (Los de abajo, translated to English as The Underdogs) is noteworthy. Poet and Nobel Laureate Octavio Paz, novelist Carlos Fuentes, Alfonso Reyes, Renato Leduc, essayist Carlos Monsiváis, journalist and public intellectual Elena Poniatowska, and Juan Rulfo (Pedro Páramo), Martín Luis Guzmán, Nellie Campobello, (Cartucho).

Mexican films from the Golden Age in the 1940s and 1950s are the greatest examples of Latin American cinema, with a huge industry comparable to the Hollywood of those years. Mexican films were exported and exhibited in all of Latin America and Europe. María Candelaria (1943) by Emilio Fernández, was one of the first films awarded a Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1946, the first time the event was held after World War II. The famous Spanish-born director Luis Buñuel realized in Mexico between 1947 and 1965 some of his masterpieces like Los Olvidados (1949) and Viridiana (1961). Famous actors and actresses from this period include María Félix, Pedro Infante, Dolores del Río, Jorge Negrete and the comedian Cantinflas.

More recently, films such as Como agua para chocolate (1992), Sex, Shame, and Tears (1999), Y tu mamá también (2001), and The Crime of Father Amaro (2002) have been successful in creating universal stories about contemporary subjects, and were internationally recognized. Mexican directors Alejandro González Iñárritu (Babel, Birdman, The Revenant, Bardo, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths), Alfonso Cuarón (A Little Princess, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, Gravity, Roma), Guillermo del Toro (Pan's Labyrinth, Crimson Peak, The Shape of Water, Nightmare Alley), screenwriter Guillermo Arriaga and photographer Emmanuel Lubezki are some of the most known present-day film makers.

Mexico has a long tradition of music from the prehispanic era to the present.Much of the music from the colonial era was composed for religious purposes.

Although the traditions of European opera and especially Italian opera had initially dominated the Mexican music conservatories and strongly influenced native opera composers (in both style and subject matter), elements of Mexican nationalism had already appeared by the latter part of the 19th century with operas such as Aniceto Ortega del Villar's 1871 Guatimotzin, a romanticized account of the defense of Mexico by its last Aztec ruler, Cuauhtémoc. The most well-known Mexican composer of the twentieth century is Carlos Chávez (1899–1978), who composed six symphonies with indigenous themes, and rejuvenated Mexican music, founding the Orquesta Sinfónica Nacional.

Traditional Mexican music includes mariachi, banda, norteño, ranchera, and corridos. Corridos were particularly popular during the Mexican Revolution (1910–20) and in the present era include narcocorridos. The embrace of rock and roll by young Mexicans in the 1960s and 1970s brought Mexico into the transnational, counterculture movement of the era. In Mexico, the native rock culture merged into the larger countercultural and political movement of the late 1960s, culminating in the 1968 protests and redirected into counterculture rebellion, La Onda (the wave).

On an everyday basis most Mexicans listen to contemporary music such as pop, rock, and others in both English and Spanish. Folk dance of Mexico along with its music is both deeply regional and traditional.Founded in 1952, the Ballet Folklórico de México performs music and dance of the prehispanic period through the Mexican Revolution in regional attire in the Palacio de Bellas Artes.

There was a major reform of the telecommunications industry in 2013, with the creation of new broadcast television channels. There had been a longstanding limitation on the number of networks, with Televisa, with a virtual monopoly; TV Azteca, and Imagen Television. New technology has allowed the entry of foreign satellite and cable companies. Mexico became the first Latin American country to transition from analog to all digital transmissions.

Telenovelas, or soap operas are very traditional in Mexico and are translated to many languages and seen all over the world. Mexico was a pioneer in edutainment, with TV producer Miguel Sabido creating in 1970s "soap operas for social change". The "Sabido method" has been adopted in many other countries subsequently, including India, Peru, Kenya, and China. The Mexican government successfully used a telenovela to promote family planning in the 1970s to curb the country's high birth rate.

Bilingual government radio stations broadcasting in Spanish and indigenous languages were a tool for indigenous education (1958–65) and since 1979 the Instituto Nacional Indigenista has established a national network of bilingual radio stations.

Organized sport in Mexico largely dates from the late nineteenth century, with only bullfighting having a long history dating to the early colonial era. Once the political turmoil of the early republic was replaced by the stability of the Porfiriato did organized sport become public diversions, with structured and ordered play governed by rules and authorities. Baseball was introduced from the United States and also via Cuba in the 1880s and organized teams were created. After the Mexican Revolution, the government sponsored sports to counter the international image of political turmoil and violence.

The bid to host the 1968 Summer Olympics was to burnish Mexico's stature internationally, with is being the first Latin American country to host the games. The government spent abundantly on sporting facilities and other infrastructure to make the games a success, but those expenditures helped fuel public discontent with the government's lack of spending on social programs. Mexico City hosted the XIX Olympic Games in 1968, making it the first Latin American city to do so. The country has also hosted the FIFA World Cup twice, in 1970 and 1986. Mexico's most popular sport is association football.

The Mexican professional baseball league is named the Liga Mexicana de Beisbol. While usually not as strong as the United States, the Caribbean countries and Japan, Mexico has nonetheless achieved several international baseball titles.

Other sporting activities include Bullfighting, boxing, and Lucha Libre (freestyle professional wrestling). Bullfighting (Spanish: corrida de toros) came to Mexico 500 years ago with the arrival of the Spanish. Despite efforts by animal rights activists to outlaw it, bullfighting remains a popular sport in the country, and almost all large cities have bullrings. Plaza México in Mexico City, which seats 45,000 people, is the largest bullring in the world. Freestyle professional wrestling is a major crowd draw with national promotions such as AAA, CMLL and others.

Mexico is an international power in professional boxing. Thirteen Olympic boxing medals have been won by Mexico.

Religion

Although the Constitutions of 1857 and 1917 put limits on the role of the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico, Roman Catholicism remains the country's dominant religious affiliation. The 2020 census by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (National Institute of Statistics and Geography) gives Roman Catholicism as the main religion, with 77.7% (97,864,218) of the population, while 11.2% (14,095,307) belong to Protestant/Evangelical Christian denominations—including Other Christians (6,778,435), Evangelicals (2,387,133), Pentecostals (1,179,415), Jehovah's Witnesses (1,530,909), Seventh-day Adventists (791,109), and members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (337,998)—; 8.1% (9,488,671) declared having no religion; .4% (491,814) were unspecified.

The 97,864,218 Catholics of Mexico constitute in absolute terms the second largest Catholic community in the world, after Brazil's. 47% percent of them attend church services weekly. The feast day of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the patron saint of Mexico, is celebrated on 12 December and is regarded by many Mexicans as the most important religious holiday of their country. The denominations Pentecostal also have an important presence, especially in the cities of the border and in the indigenous communities. As of 2010, Pentecostal churches together have more than 1.3 million adherents, which in net numbers place them as the second Christian creed in Mexico. The situation changes when the different Pentecostal denominations are considered as separate entities. Migratory phenomena have led to the spread of different aspects of Christianity, including branches Protestants, Eastern Catholic Churches and Eastern Orthodox Church.

In certain regions, the profession of a creed other than the Catholic is seen as a threat to community unity. It is argued that the Catholic religion is part of the ethnic identity, and that the Protestants are not willing to participate in the traditional customs and practices (the tequio or community work, participation in the festivities and similar issues). The refusal of the Protestants is because their religious beliefs do not allow them to participate in the cult of images. In extreme cases, tension between Catholics and Protestants has led to the expulsion or even murder of Protestants in several villages. The best known cases are those of San Juan Chamula, in Chiapas, and San Nicolás, in Ixmiquilpan, Hidalgo. A similar argument was presented by a committee of anthropologists to request the government of the Republic to expel the Summer Linguistic Institute (SIL), in the year 1979, which was accused of promoting the division of indigenous peoples by translating the Bible into vernacular languages and evangelizing in a Protestant creed that threatened the integrity of popular cultures. The Mexican government paid attention to the call of the anthropologists and canceled the agreement that had held with the SIL.

The presence of Jews in Mexico dates back to 1521, when Hernán Cortés conquered the Aztecs, accompanied by several Conversos. According to the 2020 census, there are 58,876 Jews in Mexico. Islam in Mexico (with 7,982 members) is practiced mostly by Arab Mexicans. In the 2010 census 36,764 Mexicans reported belonging to a spiritualist religion, a category which includes a tiny Buddhist population.

According to Jacobo Grinberg (in texts edited by the National Autonomous University of Mexico), the survival of magic-religious rituals of the old indigenous groups is remarkable, not only in the current indigenous population but also in the mestizo and white population that make up the Mexican rural and urban society. There is often a syncretism between shamanism and Catholic traditions. Another religion of popular syncretism in Mexico (especially in recent years) is the Santería. This is mainly due to the large number of Cubans who settled in the territory after the Cuban Revolution (mainly in states such as Veracruz and Yucatán). Even though Mexico was also a recipient of black slaves from Africa in the 16th century, the apogee of these cults is relatively new. In general, popular religiosity is viewed with bad eyes by institutionally structured religions. One of the most exemplary cases of popular religiosity is the cult of Holy Dead (Santa Muerte). The Catholic hierarchy insists on describing it as a satanic cult. However, most of the people who profess this cult declare themselves to be Catholic believers, and consider that there is no contradiction between the tributes they offer to the Christ Child and the adoration of God. Other examples are the representations of the Passion of Christ and the celebration of Day of the Dead, which take place within the framework of the Catholic Christian imaginary, but under a very particular reinterpretation of its protagonists.

Demographics

Throughout the 19th century, the population of Mexico had barely doubled. This trend continued during the first two decades of the 20th century. The 1921 census reported a loss of about 1 million inhabitants. The Mexican Revolution (c. 1910–1920) greatly impacted population increases. The growth rate increased dramatically between the 1930s and the 1980s, when the country registered growth rates of over 3% (1950–1980). The Mexican population doubled in twenty years, and at that rate it was expected that by 2000 there would be 120 million people living in Mexico. Life expectancy increased from 36 years (in 1895) to 72 years (in the year 2000). According to estimations made by Mexico's National Geography and Statistics Institute, is estimated in 2022 to be 129,150,971 as of 2017 Mexico had 123.5 million inhabitants making it the most populous Spanish-speaking country in the world.

Mexico's population is highly diverse, but research on Mexican ethnicity has felt the impact of nationalist discourses on identity. Since the 1930s, the Mexican government has promoted the view that all Mexicans are part of the Mestizo community, within which they are distinguished only by residence in or outside of an indigenous community, degree of fluency in an indigenous language, and degree of adherence to indigenous customs. Even then, across the years the government has used different criteria to count Indigenous peoples, with each of them returning considerably different numbers ranging from 6.1% to 23% of the country's population. It is not until very recently that the Mexican government began conducting surveys that consider other ethnic groups that live in the country, such as Afro-Mexicans (who comprised 2% of Mexico's population in 2020) or White Mexicans (47%). (These studies assert a view of race based on appearance rather than on self-declared ancestry). Less numerous groups in Mexico such as Asians and Middle Easterners are also accounted for, with numbers of around 1% each. While Mestizos are a prominent ethnic group in contemporary Mexico, the subjective and ever-changing definition of this category have led to its estimations being imprecise, having been observed that many Mexicans do not identify as Mestizos, favoring instead ethnoracial labels such as White or Indigenous due to having more consistent and "static" definitions.

The total percentage of Mexico's indigenous peoples tends to vary depending on the criteria used by the government in its censuses: if the ability to speak an indigenous language is used as the criterion to define a person as indigenous, it is 6.1%, if racial self-identification is used, it is 14.9% and if people who consider themselves part indigenous are also included, it amounts to 23%. Nonetheless, all the censuses conclude that the majority of Mexico's indigenous population is concentrated in rural areas of the southern and south-eastern Mexican states, with the highest percentages being found in Yucatán (59% of the population), Oaxaca (48%), Quintana Roo (39%), Chiapas (28%), and Campeche (27%).

Similarly to Mestizo and indigenous peoples, estimates of the percentage of European-descended Mexicans vary considerably depending on the criteria used: recent nationwide field surveys that account for different phenotypical traits (hair color, skin color etc.) report a percentage between 18% -23% if the criterion is the presence of blond hair, and of 47% if the criterion is skin color, with the later surveys having been conducted by Mexico's government itself. While, during the colonial era, most of the European migration into Mexico was Spanish, in the 19th and 20th centuries, a substantial number of non-Spanish Europeans immigrated to the country, with Europeans often being the most numerous ethnic group in colonial Mexican cities. Nowadays, Mexico's northern and western regions have the highest percentages of European populations, with the majority of the people not having native admixture or being of predominantly European ancestry. The Afro-Mexican population (2,576,213 individuals ) is an ethnic group made up of descendants of Colonial-era slaves and recent immigrants of sub-Saharan African descent. Mexico had an active slave trade during the colonial period, and some 200,000 Africans were taken there, primarily in the 17th century. The creation of a national Mexican identity, especially after the Mexican Revolution, emphasized Mexico's indigenous and European past; it passively eliminated the African ancestors and contributions. Most of the African-descended population was absorbed into the surrounding Mestizo (mixed European/indigenous) and indigenous populations through unions among the groups. Evidence of this long history of intermarriage with Mestizo and indigenous Mexicans is also expressed in the fact that, in the 2015 inter-census, 64.9% (896,829) of Afro-Mexicans also identified as indigenous. It was also reported that 7.4% of Afro-Mexicans speak an indigenous language. The states with the highest self-report of Afro-Mexicans were Guerrero (8.6% of the population), Oaxaca (4.7%) and Baja California Sur (3.3%). Afro-Mexican culture is strongest in the communities of the Costa Chica of Oaxaca and Costa Chica of Guerrero.

During the early 20th century, a substantial number of Arabs (mostly Christians) began arriving from the crumbling Ottoman Empire. The largest group were the Lebanese and an estimated 400,000 Mexicans have some Lebanese ancestry.

Smaller ethnic groups in Mexico include South and East Asians, present since the colonial era. During the colonial era, Asians were termed Chino (regardless of ethnicity), and arrived as merchants, artisans and slaves. A study by Juan Esteban Rodríguez, a graduate student at the National Laboratory of Genomics for Biodiversity, indicated that up to one third of people sampled from Guerrero state had significantly more Asian ancestry than most Mexicans, primarily Filipino or Indonesian. Modern Asian immigration began in the late 19th century, and at one point in the early 20th century, the Chinese were the second largest immigrant group.

Spanish is the de facto national language spoken by the vast majority of the population, making Mexico the world's most populous Hispanophone country. Mexican Spanish refers to the varieties of the language spoken in the country, which differ from one region to another in sound, structure, and vocabulary. In general, Mexican Spanish does not make any phonetic distinction among the letters s and z, as well as c when preceding the vowels e and i, as opposed to Peninsular Spanish. The letters b and v have the same pronunciation as well. Furthermore, the usage of vos, the second person singular pronoun, found in several Latin American varieties, is replaced by tú; whereas vosotros, the second person plural pronoun, fell out of use and was effectively replaced by ustedes. In written form, the Spanish Royal Academy serves as the primary guideline for spelling, except for words of Amerindian origin that retain their original phonology such as cenzontle instead of sinzontle and México not Méjico. Words of foreign origin also maintain their original spelling such as "whisky" and "film", as opposed to güisqui and filme as the Royal Academy suggests. The letter x is distinctly used in Mexican Spanish, where it may be pronounced as (as in oxígeno or taxi); as, particularly in Amerindian words (e.g. mixiote, Xola and uxmal); and as the voiceless velar fricative (such as Texas and Oaxaca).

The federal government officially recognizes sixty-eight linguistic groups and 364 varieties of indigenous languages. It is estimated that around 8.3 million citizens speak these languages, with Nahuatl being the most widely spoken by more than 1.7 million, followed by Yucatec Maya used daily by nearly 850,000 people. Tzeltal and Tzotzil, two other Mayan languages, are spoken by around half a million people each, primarily in the southern state of Chiapas. Mixtec and Zapotec, with an estimated 500,000 native speakers each, are two other prominent language groups. Since its creation in March 2003, the National Indigenous Languages Institute has been in charge of promoting and protecting the use of the country's indigenous languages, through the General Law of Indigenous Peoples' Linguistic Rights, which recognizes them de jure as "national languages" with status equal to that of Spanish. That notwithstanding, in practice, indigenous peoples often face discrimination and do not have full access to public services such as education and healthcare, or to the justice system, as Spanish is the prevailing language.

Aside from indigenous languages, there are several minority languages spoken in Mexico due to international migration such as Low German by the 80,000-strong Mennonite population, primarily settled in the northern states, fueled by the tolerance of the federal government towards this community by allowing them to set their own educational system compatible with their customs and traditions. The Chipilo dialect, a variance of the Venetian language, is spoken in the town of Chipilo, located in the central state of Puebla, by around 2,500 people, mainly descendants of Venetians that migrated to the area in the late 19th century. Furthermore, English is the most commonly taught foreign language in Mexico. It is estimated that nearly 24 million, or around a fifth of the population, study the language through public schools, private institutions or self-access channels. However, a high level of English proficiency is limited to only 5% of the population. Moreover, French is the second most widely taught foreign language, as every year between 200,000 and 250,000 Mexican students enroll in language courses.

In the early 1960s, around 600,000 Mexicans lived abroad, which increased sevenfold by the 1990s to 4.4 million. At the turn of the 21st century, this figure more than doubled to 9.5 million. As of 2017, it is estimated that 12.9 million Mexicans live abroad, primarily in the United States, which concentrates nearly 98% of the expatriate population.

The majority of Mexicans have settled in states such as California, Texas and Illinois, particularly around the metropolitan areas of Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston and Dallas–Fort Worth. As a result of these major migration flows in recent decades, around 36 million U.S. residents, or 11.2% of the country's population, identified as being of full or partial Mexican ancestry.

The remaining 2% of expatriates have settled in Canada (86,000), primarily in the provinces of Ontario and Quebec, followed by Spain (49,000) and Germany (18,000), both European destinations represent almost two-thirds of the Mexican population living in the continent. As for Latin America, it is estimated that 69,000 Mexicans live in the region, Guatemala (18,000) being the top destination for expatriates, followed by Bolivia (10,000) and Panama (5,000).

, it is estimated that 1.2 million foreigners have settled in Mexico, up from nearly 1 million in 2010. The vast majority of migrants come from the United States (900,000), making Mexico the top destination for U.S. citizens abroad. The second largest group comes from neighboring Guatemala (54,500), followed by Spain (27,600). Other major sources of migration are fellow Latin American countries, which include Colombia (20,600), Argentina (19,200) and Cuba (18,100). Historically, the Lebanese diaspora and the German-born Mennonite migration have left a notorious impact in the country's culture, particularly in its cuisine and traditional music. At the turn of the 21st century, several trends have increased the number of foreigners residing in the country such as the 2008–2014 Spanish financial crisis, increasing gang-related violence in the Northern Triangle of Central America, the ongoing political and economic crisis in Venezuela, and the automotive industry boom led by Japanese and South Korean investment.

Although the Constitutions of 1857 and 1917 put limits on the role of the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico, Roman Catholicism remains the country's dominant religious affiliation. The 2020 census by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (National Institute of Statistics and Geography) gives Roman Catholicism as the main religion, with 77.7% (97,864,218) of the population, while 11.2% (14,095,307) belong to Protestant/Evangelical Christian denominations—including Other Christians (6,778,435), Evangelicals (2,387,133), Pentecostals (1,179,415), Jehovah's Witnesses (1,530,909), Seventh-day Adventists (791,109), and members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (337,998)—; 8.1% (9,488,671) declared having no religion; .4% (491,814) were unspecified.

The 97,864,218 Catholics of Mexico constitute in absolute terms the second largest Catholic community in the world, after Brazil's. 47% percent of them attend church services weekly. The feast day of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the patron saint of Mexico, is celebrated on 12 December and is regarded by many Mexicans as the most important religious holiday of their country. The denominations Pentecostal also have an important presence, especially in the cities of the border and in the indigenous communities. As of 2010, Pentecostal churches together have more than 1.3 million adherents, which in net numbers place them as the second Christian creed in Mexico. The situation changes when the different Pentecostal denominations are considered as separate entities. Migratory phenomena have led to the spread of different aspects of Christianity, including branches Protestants, Eastern Catholic Churches and Eastern Orthodox Church.

In certain regions, the profession of a creed other than the Catholic is seen as a threat to community unity. It is argued that the Catholic religion is part of the ethnic identity, and that the Protestants are not willing to participate in the traditional customs and practices (the tequio or community work, participation in the festivities and similar issues). The refusal of the Protestants is because their religious beliefs do not allow them to participate in the cult of images. In extreme cases, tension between Catholics and Protestants has led to the expulsion or even murder of Protestants in several villages. The best known cases are those of San Juan Chamula, in Chiapas, and San Nicolás, in Ixmiquilpan, Hidalgo. A similar argument was presented by a committee of anthropologists to request the government of the Republic to expel the Summer Linguistic Institute (SIL), in the year 1979, which was accused of promoting the division of indigenous peoples by translating the Bible into vernacular languages and evangelizing in a Protestant creed that threatened the integrity of popular cultures. The Mexican government paid attention to the call of the anthropologists and canceled the agreement that had held with the SIL.

The presence of Jews in Mexico dates back to 1521, when Hernán Cortés conquered the Aztecs, accompanied by several Conversos. According to the 2020 census, there are 58,876 Jews in Mexico. Islam in Mexico (with 7,982 members) is practiced mostly by Arab Mexicans. In the 2010 census 36,764 Mexicans reported belonging to a spiritualist religion, a category which includes a tiny Buddhist population.

According to Jacobo Grinberg (in texts edited by the National Autonomous University of Mexico), the survival of magic-religious rituals of the old indigenous groups is remarkable, not only in the current indigenous population but also in the mestizo and white population that make up the Mexican rural and urban society. There is often a syncretism between shamanism and Catholic traditions. Another religion of popular syncretism in Mexico (especially in recent years) is the Santería. This is mainly due to the large number of Cubans who settled in the territory after the Cuban Revolution (mainly in states such as Veracruz and Yucatán). Even though Mexico was also a recipient of black slaves from Africa in the 16th century, the apogee of these cults is relatively new. In general, popular religiosity is viewed with bad eyes by institutionally structured religions. One of the most exemplary cases of popular religiosity is the cult of Holy Dead (Santa Muerte). The Catholic hierarchy insists on describing it as a satanic cult. However, most of the people who profess this cult declare themselves to be Catholic believers, and consider that there is no contradiction between the tributes they offer to the Christ Child and the adoration of God. Other examples are the representations of the Passion of Christ and the celebration of Day of the Dead, which take place within the framework of the Catholic Christian imaginary, but under a very particular reinterpretation of its protagonists.

In the 1930s, Mexico made a commitment to rural health care, mandating that mostly urban medical students receive training in it and to make them agents of the state to assess marginal areas. Since the early 1990s, Mexico entered a transitional stage in the health of its population and some indicators such as mortality patterns are identical to those found in highly developed countries like Germany or Japan. Mexico's medical infrastructure is highly rated for the most part and is usually excellent in major cities, but rural communities still lack equipment for advanced medical procedures, forcing patients in those locations to travel to the closest urban areas to get specialized medical care. Social determinants of health can be used to evaluate the state of health in Mexico.

State-funded institutions such as Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS) and the Institute for Social Security and Services for State Workers (ISSSTE) play a major role in health and social security. Private health services are also very important and account for 13% of all medical units in the country. Medical training is done mostly at public universities with much specializations done in vocational or internship settings. Some public universities in Mexico, such as the University of Guadalajara, have signed agreements with the U.S. to receive and train American students in medicine. Health care costs in private institutions and prescription drugs in Mexico are on average lower than that of its North American economic partners.

In 2004, the literacy rate was at 97% for youth under the age of 14, and 91% for people over 15, placing Mexico at 24th place in the world according to UNESCO.

Nowadays, Mexico's literacy rate is high, at 94.86% in 2018, up from 82.99% in 1980, with the literacy rates of males and females being relatively equal. The National Autonomous University of Mexico ranks 103rd in the QS World University Rankings, making it the best university in Mexico. After it comes the Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education as the best private school in Mexico and 158th worldwide in 2019.

Private business schools also stand out in international rankings. IPADE and EGADE, the business schools of Universidad Panamericana and of Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education respectively, were ranked in the top 10 in a survey conducted by The Wall Street Journal among recruiters outside the United States.

Cities: