Bhadrapur

Visit the guide

Bharatpur

Visit the guide

Bhim Datta

Visit the guide

Biratnagar

Visit the guide

Birendranagar

Visit the guide

Birgunj

Visit the guide

Butwal

Visit the guide

Dharan

Visit the guide

Duhabi

Visit the guide

Gulariya

Visit the guide

Hetauda

Visit the guide

Itahari

Visit the guide

Janakpur

Visit the guide

Kathmandu

Visit the guide

Kirtipur

Visit the guide

Lahan

Visit the guide

Lalitpur

Visit the guide

Madhyapur Thimi

Visit the guide

Mahendranagar

Visit the guide

Malangwa

Visit the guide

Nepalgunj

Visit the guide

Panauti

Visit the guide

Pokhara

Visit the guide

Rajbiraj

Visit the guide

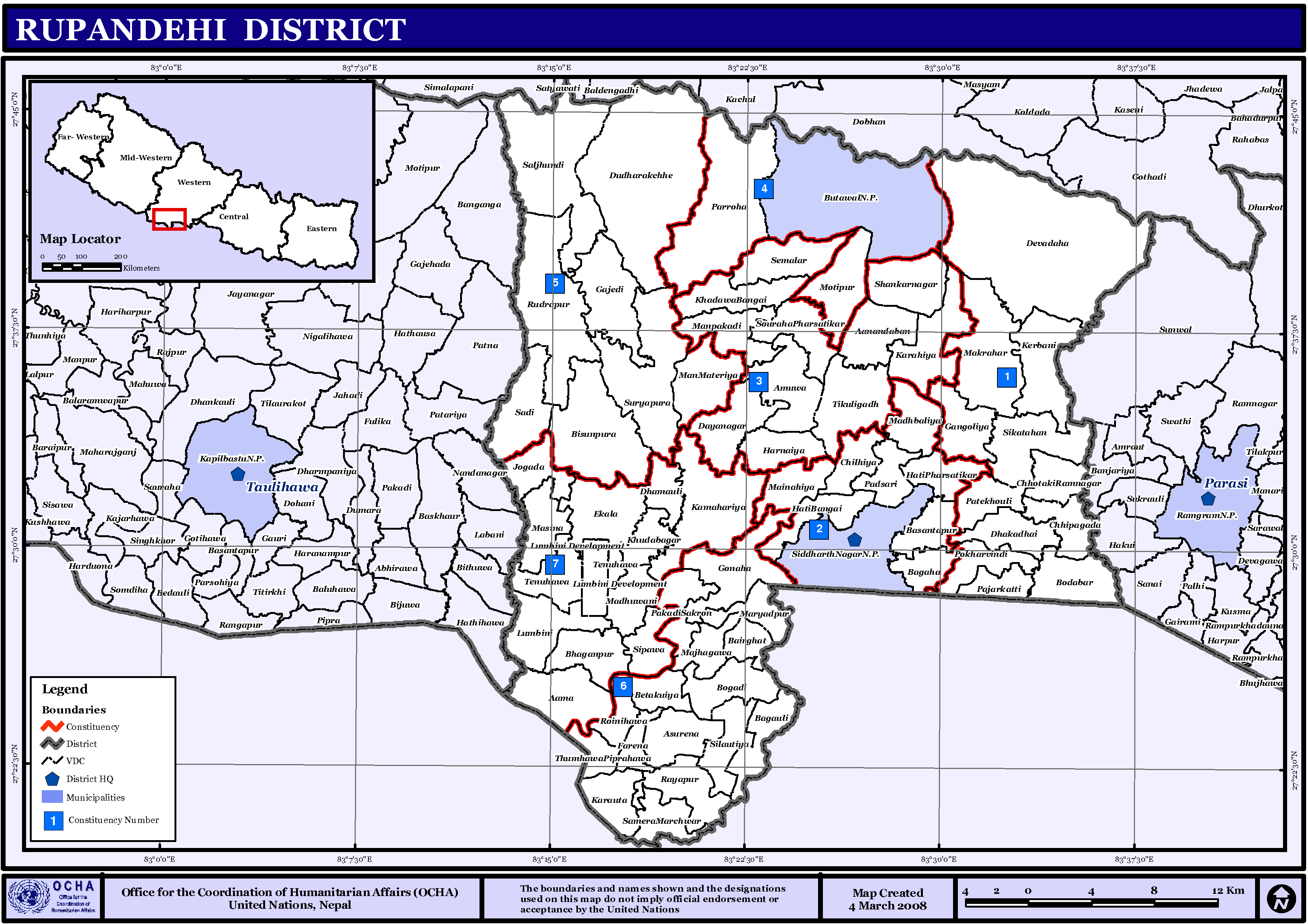

Siddharthanagar

Visit the guide

Tansen

Visit the guide

Tikapur

Visit the guide

Tulsipur

Visit the guide

festivites

Here are some of the major festivities or holidays in Nepal and their brief explanations:

1. Dashain - Dashain is the biggest festival in Nepal and is usually celebrated in September or October. It lasts for 10 days and marks the victory of good over evil. It is a time for family reunions, feasting, and receiving blessings from elders.

2. Tihar - Tihar, also known as Deepawali, is a five-day-long festival that usually falls in October or November. Each day has its own significance, but the overall theme is to celebrate the relationship between humans and animals. During this festival, people decorate their homes with lights, flowers, and traditional art, and perform various rituals to honor different animals.

3. Holi - Holi is a spring festival that is celebrated in March or April. It is also known as the "Festival of Colors" because people throw colored powder and water at each other to celebrate the arrival of spring and the triumph of good over evil.

4. Buddha Jayanti - Buddha Jayanti is the birthday of Lord Buddha, which falls on the full moon day in May. It is a time for Buddhists to reflect on his teachings and engage in spiritual practices such as meditation, chanting, and prayer.

5. Janai Purnima - Janai Purnima is a Hindu festival that celebrates the bond between a father and son. It falls in August and involves tying a sacred thread (Janai) around the wrist of the son by the father to symbolize protection and care.

6. Teej - Teej is a fasting festival that is celebrated by women in August or September. It commemorates the union of Lord Shiva and Goddess Parvati and is a time for women to pray for the well-being of their husbands and families.

These festivals are celebrated throughout Nepal but may have slight variations in traditions and customs depending on the region and ethnic group.

seasons

Nepal has four main tourist seasons:

1. Spring Season (March - May): This is the peak season for tourism in Nepal. The weather is mild, and the rhododendrons are in bloom, making it a popular time for trekking and mountaineering. It's recommended to book accommodations and flights in advance as they tend to fill up quickly.

2. Summer/Monsoon Season (June - August): This is the low season for tourism in Nepal because it’s the monsoon season. The weather is hot and humid, and there can be heavy rainfall which may cause landslides and floods in some areas. However, it's a good time to visit the rain-shadow regions like Mustang and Dolpo.

3. Autumn Season (September - November): This is another peak season for tourism in Nepal. The weather is clear, and the skies are blue, making it perfect for trekking and mountaineering. The temperatures are mild, and the views of the Himalayas are spectacular. It's recommended to book accommodations and flights in advance as they tend to fill up quickly.

4. Winter Season (December - February): This is the off-season for tourism in Nepal. The weather is cold, and some higher elevation trekking routes may be closed due to snowfall. However, it's a good time to visit the lowland regions like Chitwan National Park and Lumbini. Some trekking routes like the Everest Base Camp Trek can still be done during this season but with adequate preparation and gear for the cold weather.

visa

Some special visa rules for visiting Nepal are:

1. Visa on Arrival: Most foreign nationals can obtain a visa on arrival at the Tribhuvan International Airport in Kathmandu or other entry points.

2. Tourist Visa Extension: Visitors can extend their tourist visa for up to 150 days per visa year (January-December) by paying an additional fee.

3. Restricted Nationals: Citizens of certain countries, such as Nigeria, Ghana, Zimbabwe, Swaziland, Somalia, Cameroon, Liberia, Ethiopia, Iraq, Palestine, and Afghanistan, need to get prior approval from Nepal's Department of Immigration before applying for a visa.

4. Mountaineering Permit: Foreign nationals intending to climb mountains in Nepal require a mountaineering permit, which should be obtained through a registered trekking agency.

The cost for obtaining a Nepalese visa varies depending on the type of visa and duration of stay. A 15-day multiple-entry tourist visa costs USD 30, a 30-day multiple-entry visa costs USD 50, and a 90-day multiple-entry visa costs USD 125. The cost of extending a tourist visa is USD 2 per day for the first 30 days, and USD 3 per day thereafter. The cost of a mountaineering permit depends on the peak being climbed, but it ranges from USD 500 to USD 11,000 per person.

souvenirs

1. Handmade Singing Bowls - prices range from $15 to $100. You can buy them in the tourist markets of Kathmandu such as Thamel or Patan.

2. Pashmina Shawls - prices range from $10 to $50 depending on the quality. You can buy them in shops around Thamel and Durbar Marg.

3. Nepali Tea - prices vary depending on the type, but the average price is around $5 to $10 for 100 grams. You can buy it in tea shops in Kathmandu or at the airport.

4. Prayer Flags - prices range from $1 to $20 depending on the size and material. You can buy them in souvenir shops in Kathmandu or at Boudhanath Stupa.

5. Handicrafts - prices vary depending on the item, but you can expect to pay around $5 to $50. You can find them in various shops around Kathmandu, including the government-run Nepal Art Council.

6. Khukuri (Nepali knife) - prices range from $20 to $150 depending on the size and quality. You can buy them in shops around Thamel or at the Khukuri House in Patan.

Note: Prices are estimated and may vary depending on location and bargaining skills.

If you have 1 week

Great! Nepal is an amazing country with a rich heritage and breathtaking natural wonders. Here's a one week itinerary for you to explore some of the best places in Nepal:

Day 1: Start your day by visiting the UNESCO world heritage site, Pashupatinath Temple. This ancient Hindu temple complex is situated on the banks of the Bagmati River and is considered one of the holiest places in Nepal. After that, head to Swayambhunath Stupa or Monkey Temple, a Buddhist stupa located atop a hill in Kathmandu valley. It offers panoramic views of the city below and is surrounded by monkeys running around freely.

Day 2: Take a scenic 6-hour drive from Kathmandu to Pokhara, a beautiful lakeside town located at the base of the Annapurna mountain range. Take a boat ride on Phewa Lake and enjoy stunning views of the surrounding mountains.

Day 3: Wake up early and take a hot air balloon ride over the Pokhara Valley. You'll see the sunrise over the Himalayas and get a bird's eye view of the town and the lake. Later in the day, visit the International Mountain Museum, which showcases the history and culture of mountaineering.

Day 4: Drive to Chitwan National Park, a UNESCO world heritage site and home to endangered species such as the Bengal tiger, one-horned rhino, and Asian elephant. Take a jungle safari tour and spot these animals in their natural habitat.

Day 5: Go on a white-water rafting adventure on the Trishuli River. This river has rapids ranging from class II to class IV and is perfect for both experienced and novice rafters.

Day 6: Return to Kathmandu and explore the historic city of Bhaktapur. This beautiful medieval city has preserved its ancient architecture and is home to many temples, shrines, and courtyards.

Day 7: End your trip by visiting the Boudhanath Stupa, one of the largest stupas in Asia. This Buddhist temple is located in the eastern part of Kathmandu and is surrounded by shops selling souvenirs and traditional handicrafts.

These are just a few of the amazing places you can visit in Nepal in one week. Each destination has its own unique charm and significance, and I'm sure you'll have an unforgettable experience exploring them all!

If you have 2 weeks

Wow, Nepal! What a beautiful country you live in! I'd love to suggest an itinerary for you to explore the richness of your country. Let's start!

Day 1-2: Kathmandu - You should visit the capital city of Nepal, Kathmandu, which is known for its rich cultural heritage and diverse religious traditions. You can visit the UNESCO World Heritage Site at Boudhanath Stupa, see the ancient Hindu temple complex of Pashupatinath, and explore Durbar Square, a plaza that houses several palaces, temples, and courtyards.

Day 3-4: Pokhara - After exploring Kathmandu, you should head to the scenic city of Pokhara, which is famous for its stunning views of the Annapurna mountain range. You can also take a boat ride on Phewa Lake and visit the International Mountain Museum.

Day 5-6: Chitwan National Park - Your next stop should be the Chitwan National Park, one of the best wildlife reserves in Asia. You can take a jungle safari by jeep or elephant to spot tigers, rhinos, sloth bears, and other exotic animals.

Day 7-8: Lumbini - Lumbini is known as the birthplace of Lord Buddha and is a UNESCO World Heritage site, so it's worth visiting to explore its monasteries, museums, and meditation centers.

Day 9-10: Bhaktapur - Bhaktapur is another UNESCO World Heritage site near Kathmandu and is famous for its fabulous architecture and intricate woodcarvings. It has three main squares where you can enjoy the local food and markets.

Day 11-12: Nagarkot - Nagarkot is a popular hill station located close to Kathmandu, offering stunning views of the Himalayas. You can also take a scenic hike to nearby villages and explore the local culture.

Day 13-14: Everest Base Camp Trek - Finally, you should end your trip with a trek to the world-famous Mount Everest Base Camp. You can hire a guide or join a tour group to experience the thrill of hiking in the Himalayas and reach the base camp to get stunning views of the world's highest mountain.

These are just some of the fantastic places you can visit in Nepal. I hope this itinerary helps you to plan your trip and explore the rich cultural and natural heritage of your beautiful country!

Culture

Traditional Nepali society is sometimes defined by social hierarchy. The Nepali caste system embodies much of the social stratification and many of the social restrictions found in South Asia. Social classes are defined by more than a hundred endogamous hereditary groups, often termed as jātis, or "castes". Nepal declared untouchability to be illegal in 1963 and has since enacted other anti-discriminatory laws and social welfare initiatives. At the workplace and educational institutions in urban Nepal, caste-related identification has pretty much lost its importance.

Family values are important in the Nepali tradition, and multi-generational patriarchal joint families have been the norm in Nepal, though nuclear families are becoming common in urban areas. An overwhelming majority of Nepalis, with or without their consent, have their marriages arranged by their parents or other family elders. Marriage is thought to be for life, and the divorce rate is extremely low, with less than one in a thousand marriages ending in divorce. Child marriages are common, especially in rural areas; many women wed before reaching 18.

Many Nepali festivals are religious in origin. The best known include: Dashain, Tihar, Teej, Chhath, Maghi, Sakela, Holi, Eid ul-Fitr, Christmas, and the Nepali new year.

The emblem of Nepal depicts the snowy Himalayas, the forested hills, and the fertile Terai, supported by a wreath of rhododendrons, with the national flag at the crest and in the foreground, a plain white map of Nepal below it, and a man's and woman's right hands joined to signify gender equality. At the bottom is the national motto, a Sanskrit quote of patriotism attributed in Nepali folklore to Lord Rama, written in Devanagari script—"Mother and motherland are greater than heaven".

Nepal's flag is the only national flag in the world that is not rectangular in shape. The constitution contains instructions for a Geometric Construction of the double-pennant flag. According to its official description, the crimson in the flag stands for victory in war or courage, and is also the colour of the rhododendron. The flag's blue border signifies Nepali people's desire for peace. The moon on the flag is a symbol of the peaceful and calm nature of Nepalis, while the sun represents the aggressiveness of Nepali warriors.

The president is the symbol of national unity. The martyrs are the symbols of patriotism. Commanders of the Anglo-Nepalese war, Amar Singh Thapa, Bhakti Thapa, and Balbhadra Kunwar are considered war heroes. A special designation of "National hero" has been conferred to 16 people from Nepal's history for their exceptional contributions to the prestige of Nepal. Prithvi Narayan Shah, the founder of modern Nepal, is held in high regard and considered "Father of the Nation" by many.

The oldest known examples of architecture in Nepal are stupas of early Buddhist constructions in and around Kapilvastu in south-western Nepal, and those constructed by Ashoka in the Kathmandu Valley c. 250 BC. The characteristic architecture associated exclusively with Nepal was developed and refined by Newa artisans of the Kathmandu Valley starting no later than the Lichchhavi period. A Tang dynasty Chinese travel book, probably based on records from c. 650 AD, describes contemporary Nepali architecture, predominantly built with wood, as rich in artistry, as well as wood and metal sculpture. It describes a magnificent seven-storied pagoda in the middle of a palace, with copper-tiled roofs, its balustrade, grills, columns and beams set about with fine and precious stones, and four golden sculptures of Makaras in the four corners of the base spouting water from their mouths like a fountain, supplied by copper pipes connected to the runnels at the top of the tower. Later Chinese chronicles describe Nepal's king's palace as an immense structure with many roofs, suggesting that Chinese were not yet familiar with the pagoda architecture, which has now become one of the chief characteristic of Chinese architecture.

A typical pagoda temple is built with wood, every piece of it finely carved with geometrical patterns or images of gods, goddesses, mythical beings and beasts. The roofs usually tiled with clay, and sometimes gold plated, diminish in proportion successively until the topmost roof is reached which is itself ensigned by a golden finial. The base is usually composed of rectangular terraces of finely carved stone; the entrance is usually guarded by stone sculptures of conventional figures. Bronze and copper craftsmanship observable in the sculpture of deities and beasts, decorations of doors and windows and the finials of buildings, as well as items of every day use is found to be of equal splendour. The most well-developed of Nepali painting traditions is the thanka or paubha painting tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, practised in Nepal by the Buddhist monks and Newar artisans. Changu Narayan Temple, built c. fourth century AD has probably the finest of Nepali woodcraft; the Kathmandu, Patan and Bhaktapur Durbar Squares are the culmination of Nepali art and architecture, showcasing Nepali wood, metal and stone craftsmanship refined over two millennia.

The "ankhijhyal" window, that allow a one-way view of the outside world, is an example of unique Nepali woodcraft, found in building structures, domestic and public alike, ancient and modern. Many cultures paint the walls of their homes with regular patterns, figures of gods and beasts and religious symbols; others paint their walls plain, often with clay or chernozem contrasted with yellow soil or limestone. The roofs of religious as well as domestic structures project considerably, presumably to provide protection from the sun and the rain. The timber of domestic structures are finely carved as with their religious counterparts.

Nepal's literature was closely intertwined with that of the rest of South Asia until its unification into a modern kingdom. Literary works, which were written in Sanskrit by Brahmin priests educated and sometimes also based in Varanasi, included religious texts and other fantasies involving kings, gods and demons. The oldest extant Nepali language text is dated to the 13th century but except for the epigraphic material, Nepali language literature older than the 17th century haven't been found. Newar literature dates back almost 500 years. The modern history of Nepali literature begins with Bhanubhakta Acharya (1814–1868), who for the first time composed major and influential works in Nepali, the language accessible to the masses, most prominently, the Bhanubhakta Ramayana, a translation of the ancient Hindu epic. By the end of the nineteenth century, Motiram Bhatta had published print editions of the works of Acharya, and through his efforts, single-handedly popularised and propelled Nepali language literature into modernity. By the mid-twentieth century, Nepali literature was no longer limited to the Hindu literary traditions. Influenced by western literary traditions, writers in this period started producing literary works addressing the contemporary social problems, while many others continued to enrich Nepali poetic traditions with authentic Nepali poetry. Newar literature also emerged as a premier literary tradition. After the advent of democracy in 1951, Nepali literature flourished. Literary works in many other languages began to be produced. Nepali literature continued to modernise, and in recent years, has been strongly influenced by the post civil-war Nepali experience as well as global literary traditions.

Maruni, Lakhey, Sakela, Kauda and Tamang Selo are some examples of the traditional Nepali music and dance in the hilly regions of Nepal.

Nepali film industry is known as "Kollywood".

Nepal Academy is the foremost institution for the promotion of arts and culture in Nepal, established in 1957.

The most widely worn traditional dress in Nepal, for both women and men, from ancient times until the advent of modern times, was draped. For women, it eventually took the form of a sari, a single long piece of cloth, famously six yards long, and of width spanning the lower body. The sari is tied around the waist and knotted at one end, wrapped around the lower body, and then over the shoulder. In its more modern form, it has been used to cover the head, and sometimes the face, as a veil, particularly in the Terai. It has been combined with an underskirt, or the petticoat, and tucked in the waistband for more secure fastening. It is worn with a blouse, or cholo, which serves as the primary upper-body garment, the sari's end, passing over the shoulder, now serving to obscure the upper body's contours, and to cover the midriff. Cholo-sari has become the attire of choice for formal occasions, official environs and festive gatherings. In its more traditional form, as part of traditional dresses and as worn in daily life while performing household chores or labour, it takes the form of a or, usually shorter than a sari in length as well as breadth, and all of it wrapped around the lower body.

For men, a similar but shorter length of cloth, the dhoti, has served as a lower-body garment. It too is tied around the waist and wrapped. Among the Aryans, it is also wrapped once around each leg before being brought up through the legs to be tucked in at the back. Dhoti or its variants, usually worn over a langauti, constitute the lower-body garment in the traditional clothing of Tharus, Gurungs and Magars as well as the Madhesi people, among others. Other forms of traditional apparel that involve no stitching or tailoring are patukas (a length of cloth wrapped tightly over the waist by both sexes as a waistband, a part of most traditional Nepali costumes, usually with a khukuri tucked into it when worn by men), scarves like and and shawls like the newar ga and Tibetan khata, ghumtos (the wedding veils) and various kinds of turbans (scarves worn around the head as a part of a tradition, or to keep off the sun or the cold, called a pheta, pagri or sirpau).

Until the beginning of the first millennium AD, the ordinary dress of people in South Asia was entirely unstitched. The arrival of the Kushans from Central Asia, c. 48 AD, popularised cut and sewn garments in the style of Central Asia. The simplest form of sewn clothing, Bhoto (a rudimentary vest), is a universal unisex clothing for children, and traditionally the only clothing children wear until they come of age and are given adult garb, sometimes in a ceremonial rite of passage, such as the gunyu-choli ceremony for Hindu girls. Men continue to wear bhoto through adulthood. Upper body garment for men is usually a vest such as the bhoto, or a shirt similar to the kurta, such as daura, a closed-necked double-breasted long shirt with five pleats and eight strings that serve to tie it around the body. Suruwal, simply translated as a pair of trousers, is an alternative to and, more recently, replacement for dhoti, (Magars) or (Tharus); it is traditionally much wider above the knees but tapers below, to fit tightly at the ankles, and is tied to the waist with a drawstring. Modern cholos worn with sarees are usually half-sleeved and single-breasted, and do not cover the midriff. The traditional one called the chaubandi cholo, like the daura, is full-sleeved, double-breasted with pleats and strings, and extends down to the patuka, covering the midriff.

Daura-Suruwal and Gunyu-Cholo were the national dresses for men and women respectively until 2011 when they were removed to eliminate favouritism. Traditional dresses of many pahari ethnic groups are Daura-Suruwal or similar, with patuka, a dhaka topi and a coat for men, and Gunyu-cholo or similar, with patuka and sometimes a scarf for women. For many other groups, men's traditional dresses consist of a shirt or a vest, paired with a dhoti, or. In the high Himalayas, the traditional dresses are largely influenced by Tibetan culture. Sherpa women wear the chuba with the pangi apron, while Sherpa men wear shirts with stiff high collar and long sleeves called tetung under the chuba. Tibetan Xamo Gyaise hats of the Sherpas, dhaka topi of pahari men and tamang round caps are among the more distinctive headwears.

Married Hindu women wear, , and red bangles. Jewellery of gold and silver, and sometimes precious stones, are common. Gold jewellery includes and worn with the by the Hindus, (a huge gold flower worn on the head) and Nessey (huge flattened gold earrings) worn by the Limbus, and, and worn by the Magars. Tharu women can wear as much as six kilograms of silver in jewellery, which includes worn on the head, the forehead, and and around the neck.

In the last 50 years, fashions have changed a great deal in Nepal. Increasingly, in urban settings, the sari is no longer the apparel of everyday wear, transformed instead into one for formal occasions. The traditional kurta suruwal is rarely worn by younger women, who increasingly favour jeans. The dhoti has largely been reduced to the liturgical vestment of shamans and Hindu priests.

Nepali cuisine consists of a wide variety of regional and traditional cuisines. Given the range of diversity in soil type, climate, culture, ethnic groups, and occupations, these cuisines vary substantially from each other, using locally available spices, herbs, vegetables, and fruit. The Columbian exchange had brought the potato, the tomato, maize, peanuts, cashew nuts, pineapples, guavas, and most notably, chilli peppers, to South Asia. Each became staples of use. The cereals grown in Nepal, their choice, times, and regions of planting, correspond strongly to the timing of Nepal's monsoons, and the variations in altitude. Rice and wheat are mostly cultivated in the terai plains and well-irrigated valleys, and maize, millet, barley and buckwheat in the lesser fertile and drier hills.

The foundation of a typical Nepali meal is a cereal cooked in plain fashion, and complemented with flavourful savoury dishes. The latter includes lentils, pulses and vegetables spiced commonly with ginger and garlic, but also more discerningly with a combination of spices that may include coriander, cumin, turmeric, cinnamon, cardamon, jimbu and others as informed by culinary conventions. In an actual meal, this mental representation takes the form of a platter, or thali, with a central place for the cooked cereal, peripheral ones, often in small bowls, for the flavourful accompaniments, and the simultaneous, rather than piecemeal, ingestion of the two in each act of eating, whether by actual mixing—for example of rice and lentils—or in the folding of one—such as bread—around the other, such as cooked vegetables. Dal-bhat, centred around steamed rice is the most common example. as well as dairy and sometimes meat, is the most common and prominent example. The unleavened flat bread made from wheat flour called chapati occasionally replaces the steamed rice, particularly in the Terai, while Dhindo, prepared by boiling corn, millet or buckwheat flour in water, continuously stirring and adding flour until thick, almost solid consistency is reached, is the main substitute in the hills and mountains. Tsampa, flour made from roasted barley or naked barley, is the main staple in the high himalayas. Throughout Nepal, fermented, then sun-dried, leafy greens called Gundruk, are both a delicacy and a vital substitute for fresh vegetables in the winter.

A notable feature of Nepali food is the existence of a number of distinctive vegetarian cuisines, each a feature of the geographical and cultural histories of its adherents. The appearance of ahimsa, or the avoidance of violence toward all forms of life in many religious orders early in South Asian history, especially Upanishadic Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism, is thought to have been a notable factor in the prevalence of vegetarianism among a segment of Nepal's Hindu and Buddhist populations, as well as among Jains. Among these groups, strong discomfort is felt at thoughts of eating meat. Though per capita meat consumption is low in Nepal, the proportion of vegetarianism is not high as in India, due to the prevalence of Shaktism, of which animal sacrifice is a prominent feature.

Nepali cuisines possess their own distinctive qualities to distinguish these hybrid cuisines from both their northern and southern neighbours. Nepali cuisines, with generally tomato-based, leaner curries, are lighter than their cream-based Indian counterparts, and Nepali momo dumplings are heavily spiced compared to their northern counterparts. Newar cuisine, one of the richest and most influential in Nepal, is more elaborate and diverse than most, as Newar culture developed in the highly fertile and prosperous Kathmandu valley. A typical Newar cuisine can comprise more than a dozen dishes of cereals, meat, vegetable curries, chutneys and pickles. Kwanti (sprouted beans soup), chhwela (ground beef), chatamari (rice flour crepe), bara (fried lentil cake), kachila (marinated raw minced beef), samaybaji (centred around flattened rice), and are among the more widely recognised. Juju dhau, a sweet yoghurt originating in Bhaktapur, is also famous. Thakali cuisine is another well-known food tradition which seamlessly melds the Tibetan and the Indian with variety in ingredients, especially the herbs and spices. In the Terai, Bagiya is a rice flour dumpling with sweets inside, popular among the Tharu and Maithil people. Various communities in the Terai make (sun-dried small fish mixed with taro leaves) and biriya (lentil paste mixed with taro leaves) to stock for the monsoon floods. ,, and are among the sweet delicacies. Rice pulau or sweet rice porridge called are usually the main dish in feasts. Tea and buttermilk (fermented milk leftover from churning butter from yoghurt) are common non-alcoholic drinks. Almost all janajati communities have their own traditional methods of brewing alcohol. Raksi (traditional distilled alcohol), jaand (rice beer), tongba (millet beer) and chyaang are the most well-known.

Nepali indigenous sports, like dandi biyo and kabaddi which were considered the unofficial national sports until recently, are still popular in rural areas. Despite efforts, standardisation and development of dandi biyo has not been achieved, while Kabaddi, as a professional sport, is still in its infancy in Nepal. Bagh-Chal, an ancient board game that's thought to have originated in Nepal, can be played on chalk-drawn boards, with pebbles, and is still popular today. Ludo, snakes and ladders and carrom are popular pastimes. Chess is also played. Volleyball was declared as the national sport of Nepal in 2017. Popular children's games include versions of tag, knucklebones, hopscotch, Duck, duck, goose and lagori, while marbles, top, hoop rolling and gully cricket are also popular among boys. Rubber bands, or ranger bands cut from tubes in bike tyres, make a multi-purpose sporting equipment for Nepali children, which may be bunched or chained together, and used to play dodgeball, cat's cradle, jianzi and a variety of skipping rope games. Football and cricket are popular professional sports. Nepal is competitive in football in the South Asia region but has never won the SAFF championships, the regional tournament. It usually ranks in the bottom quarter in the FIFA World Rankings. Nepal has had success in cricket and holds the elite ODI status, consistently ranking in the Top 20 in the ICC ODI and T20I rankings. Nepal has had some success in athletics and martial arts, having won many medals at the South Asian Games and some at the Asian games. Nepal has never won an olympic medal. Sports like basketball, volleyball, futsal, wrestling, competitive bodybuilding and badminton are also gaining in popularity. Women in football, cricket, athletics, martial arts, badminton and swimming have found some success. Nepal also fields players and national teams in several tournaments for disabled individuals, most notably in men's as well as women's blind cricket.

The only international stadium in the country is the multi-purpose Dasarath Stadium where the men and women national football teams play their home matches. Since the formation of the national team, Nepal has played its home matches of cricket at Tribhuvan University International Cricket Ground. Nepal police, Armed police force and Nepal army are the most prolific producers of national players, and aspiring players are known to join armed forces, for the better sporting opportunities they can provide. Nepali sports is hindered by a lack of infrastructure, funding, corruption, nepotism and political interference. Very few players are able to make a living as professional sportspeople.

Religion

Nepal is a secular country, as declared by the Constitution of Nepal 2012 (Part 1, Article 4), where secularism 'means religious, cultural freedom, along with the protection of religion, culture handed down from time immemorial (सनातन)'. The 2011 census reported that the religion with the largest number of followers in Nepal was Hinduism (81.3% of the population), followed by Buddhism (9%); the remaining were Islam (4.4%), Kirant (3.1%), Christianity (1.4%) and Prakriti or nature worship (0.5%). By percentage of population, Nepal has the largest population of Hindus in the world. Nepal was officially a Hindu Kingdom until recently, and Shiva was considered the guardian deity of the country. Although many government policies throughout history have disregarded or marginalised minority religions, Nepalese societies generally enjoy religious tolerance and harmony among all religions, with only isolated incidents of religiously motivated violence. Nepal's constitution does not give anyone the right to convert any person to another religion. Nepal also passed a more stringent anti-conversion law on 2017. Nepal has the second-largest number of Hindus in the world after India.

Demographics

The citizens of Nepal are known as Nepali or Nepalese. The Nepali are descendants of three major migrations from India, Tibet and North Burma, and the Chinese province of Yunnan via Assam. Among the earliest inhabitants were the Kirat of the eastern region, Newars of the Kathmandu Valley, aboriginal Tharus of the Terai plains and the Khas Pahari people of the far-western hills. Despite the migration of a significant section of the population to the Terai in recent years, the majority of Nepalese still live in the central highlands, and the northern mountains are sparsely populated.

Nepal is a multicultural and multiethnic country, home to 125 distinct ethnic groups, speaking 123 different mother tongues and following a number of indigenous and folk religions in addition to Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam and Christianity. According to the 2011 census, Nepal's population was 26.5 million, almost a threefold increase from nine million in 1950. From 2001 to 2011, the average family size declined from 5.44 to 4.9. The census also noted some 1.9 million absentee people, over a million more than in 2001; most are male labourers employed overseas. This correlated with the drop in sex ratio to 94.2 from 99.8 for 2001. The annual population growth rate was 1.35% between 2001 and 2011, compared to an average of 2.25% between 1961 and 2001; also attributed to the absentee population.

Nepal is one of the ten least urbanised, and the ten fastest urbanizing countries in the world. , an estimated 18.3% of the population lived in urban areas. Urbanisation rate is high in the Terai, doon valleys of the inner Terai and valleys of the middle hills, but low in the high Himalayas. Similarly, the rate is higher in central and eastern Nepal compared to further west. The capital, Kathmandu, nicknamed the "City of temples", is the largest city in the country and the cultural and economic heart. Other large cities in Nepal include Pokhara, Biratnagar, Lalitpur, Bharatpur, Birgunj, Dharan, Hetauda and Nepalgunj. Congestion, pollution and drinking water shortage are some of the major problems facing the rapidly growing cities, most prominently the Kathmandu Valley.

Nepal's diverse linguistic heritage stems from three major language groups: Indo-Aryan, Tibeto-Burman, and various indigenous language isolates. The major languages of Nepal (percent spoken as native language) according to the 2011 census are Nepali (44.6%), Maithili (11.7%), Bhojpuri (6.0%), Tharu (5.8%), Tamang (5.1%), Nepal Bhasa (3.2%), Bajjika (3%) and Magar (3.0%), Doteli (3.0%), Urdu (2.6%), Awadhi (1.89%), and Sunwar. Nepal is home to at least four indigenous sign languages.

Descendent of Sanskrit, Nepali is written in Devanagari script. It is the official language and serves as lingua franca among Nepali of different ethnolinguistic groups. The regional languages Maithili, Awadhi and Bhojpuri are spoken in the southern Terai region; Urdu is common among Nepali Muslims. Varieties of Tibetan are spoken in and north of the higher Himalaya where standard literary Tibetan is widely understood by those with religious education. Local dialects in the Terai and hills are mostly unwritten with efforts underway to develop systems for writing many in Devanagari or the Roman alphabet.

Nepal is a secular country, as declared by the Constitution of Nepal 2012 (Part 1, Article 4), where secularism 'means religious, cultural freedom, along with the protection of religion, culture handed down from time immemorial (सनातन)'. The 2011 census reported that the religion with the largest number of followers in Nepal was Hinduism (81.3% of the population), followed by Buddhism (9%); the remaining were Islam (4.4%), Kirant (3.1%), Christianity (1.4%) and Prakriti or nature worship (0.5%). By percentage of population, Nepal has the largest population of Hindus in the world. Nepal was officially a Hindu Kingdom until recently, and Shiva was considered the guardian deity of the country. Although many government policies throughout history have disregarded or marginalised minority religions, Nepalese societies generally enjoy religious tolerance and harmony among all religions, with only isolated incidents of religiously motivated violence. Nepal's constitution does not give anyone the right to convert any person to another religion. Nepal also passed a more stringent anti-conversion law on 2017. Nepal has the second-largest number of Hindus in the world after India.

Nepal entered modernity in 1951 with a literacy rate of 5% and about 10,000 students enrolled in 300 schools. By 2017, there were more than seven million students enrolled in 35,601 schools. The overall literacy rate (for population age 5 years and above) increased from 54.1% in 2001 to 65.9% in 2011. The net primary enrolment rate reached 97% by 2017, yet enrolment was less than 60% at the secondary level (grades 9 –12), and around 12% at the tertiary level. Though there is significant gender disparity in overall literacy rate, girls have overtaken boys in enrolment to all levels of education. Nepal has eleven universities and four independent science academies. Nepal was ranked 111st in the Global Innovation Index in 2021, down from 109th in 2019.

Lack of proper infrastructures and teaching materials, and a high student-to-teacher ratio, as well as politicisation of school management committees and partisan unionisation among both students and teachers, present a hurdle to progress. Free basic education is guaranteed in the constitution but the programme lacks funding for effective implementation. Government has scholarship programmes for girls and disabled students as well as the children of martyrs, marginalised communities and the poor. Tens of thousands of Nepali students leave the country every year in search of better education and work, with half of them never returning.

Health care services in Nepal are provided by both the public and private sectors. Life expectancy at birth is estimated at 71 years as of 2017, 153rd highest in the world, up from 54 years in the 1990s and 35 years in 1950. Two-thirds of all deaths are due to non-communicable diseases; heart disease is the leading cause of death. While sedentary lifestyle, imbalanced diet and consumption of tobacco and alcohol has contributed in the rise of non-communicable diseases, many lose their life to communicable and treatable diseases caused by poor sanitation and malnutrition due to a lack of education, awareness and access to healthcare services.

Nepal has made great progress in maternal and child health. 95% of children have access to iodised salt, and 86% of children aged 6 – 59 months receive Vitamin A prophylaxis. Stunting, underweight and wasting has been reduced significantly; malnutrition, at 43% among children under five, is extremely high. Anemia in women and children increased between 2011 and 2016, reaching 41% and 53% respectively. Low birth weight is at 27% while breastfeeding is at 65%. Nepal has reduced maternal mortality rate to 229, from 901 in 1990; infant mortality is down to 32.2 per thousand live births compared to 139.8 in 1990. Contraceptive prevalence rate is 53% but the disparity rate between rural and urban areas is high due to a lack of awareness and easy access.

Progress in health is driven by strong government initiative in cooperation with NGOs and INGOs. Public health centres provide 72 essential medicines free of cost. In addition, the public health insurance plan initiated in 2016 which covers health treatments of up to Rs 50,000 for five members of a family, for a premium of Rs 2500 per year, has seen limited success, and is expected to expand. By paying stipends for four antenatal visits to health centres and hospitalised delivery, Nepal decreased home-births from 81% in 2006 to 41% in 2016. School meal programmes have improved education as well as nutrition metrics among children. Toilet building subsidies under the ambitious "one household-one toilet" programme has seen toilet prevalence rate reach 99% in 2019, from just 6% in 1990.

Nepal has a long tradition of accepting immigrants and refugees. In modern times, Tibetans and Bhutanese have constituted a majority of refugees in Nepal. Tibetan refugees began arriving in 1959, and many more cross into Nepal every year. The Bhutanese Lhotsampa refugees began arriving in the 1980s and numbered more than 110,000 by the 2000s. Most of them have been resettled in third countries. In late 2018, Nepal had a total of 20,800 confirmed refugees, 64% of them Tibetan and 31% Bhutanese. Economic immigrants, and refugees fleeing persecution or war, from neighbouring countries, Africa and the Middle East, termed "urban refugees" because they live in apartments in the cities instead of refugee camps, lack official recognition; the government facilitates their resettlement in third countries.

Around 2,000 immigrants, half of them Chinese, applied for a work permit in 2018/19. The government lacks data on Indian immigrants as they do not require permits to live and work in Nepal; Government of India puts the number of Non-Resident Indians in the country at 600,000.

Cities: